TRAGEN.Hz – Oratorio Ratures

Céline Pierre

Summary :

1. 1. The Text of the Project as a Whole

2. The Video/Electroacoustic

3. The Images

Biography

1. The Text of the Project as a Whole

TRAGEN.Hz – ondes portées – oratorio ratures [carried waves – erasures].

Soundrecordings, videos, conception and composition : Celine Pierre.

Through a subject pertaining to the current events and European history, a creation which emerges from a collection of images, sounds and texts from the Calais migrant camp. The work carried out at the Reims Regional Conservatory and Centre National de Création Musicale Césaré gave rise to a series of electroacoustic and video pieces, mix-media pieces and performances for pluri-disciplinary sites and scenes.

“At a time when the world is being ever more de-realized by the spectacle of its own display, at a time when ‘the world is gone’, there are something singular that in Calais has been experienced by all those who came to meet the migrants; there, with those who are out of any home, is given to share something real. Through the voice, that of migrants, of reading and singing, the project tries to say a little – what’s left – about this.” (Lp for Tragen.Hz)

“TRAGEN.HZ – ondes portées – oratorio ratures” for multiple performances: “HZ” symbolizes the Hertzian waves. “TRAGEN” means to carry in German. The title could therefore be translated as “waves carried”. “HZ” could be the acronym for “Hertz”, the heart in German. As Paul Celan wrote: “Die Welt ist fort ich muss dich tragen”. The world is gone I must carry it. “Oratorio ratures”: in the subtitle, one word taken from the sound register, another from the visible – the erasure as a hiatus, an opening through which images and sounds can respond to each other. An option and a sharing of the sensitive inseparably poetic and political.

Writing the project calls for sequence shots of the Calais camp recorded during its dismantling, fires, earth and burnt grounds; and a corpus of sound sequences linked by the scream: screams and stridencies of the stringed instrument, screams stemming from the tradition of mourning songs and lyrical singing, a scream that carries what remains silent and is erased in all writing, that calls for voices, carries them from complaint to lament, even to consolation. All of these constituents provoke a suspension of time and space, in which resound convocations, evocations and disappearance of anonymous voices. An evocation in the tradition of the oratorio, which through one of its origins, the « lauda »- a monodic hymn written in the thirteenth century by penitents who walked through devastated lands – is part of this long history of migration and war. Path, sand, soil and ashes, everything lightly touches in a situation of erasure where the voice seeks to make its way and where time stretches in the direction of the poem:

“Poems thus move also along the pathways, they set a course, where to? Onto something that is open, available, in which you have someone to talk to, a reality to talk to” writes Paul Celan. (Lp for Tragen.Hz)

A production of LES SEPTANTES/laboratory of multiple writings.

The project is realized at he Laboratoire de Composition of the CRR-Reims [Composition Laboratory of the Reims Regional Conservatory] and in residency at the Centre National de Création Musicale Césaré-Reims; the projet is supported by “Help to Création & Diffusion Visual Arts” of the Region “Grand Est” and by “Help to Music Project” at the DRAC “Grand Est”.

2. The Video/Electroacoustic

https://vimeo.com/291877311

code TRAGEN.HZ

Presentation of the video:

TRAGEN.HZ – oratorio ratures [erasures]:

Voice and video sequences recorded in a refugee camp on the French-English border and sequences of screams, alterations and instrumental and vocal iterations recorded in studio. Whole entity that expresses what is silent and erased in all writing, which, from complaint to lament, summons the voices and provokes a suspension of time and space in which convocations, evocations, and disappearance of anonymous voices resound.

Conception, collected material, and visual and sound composition: Celine Pierre. Voices: Thierry Machuel, Caroline Chassagny and voices recorded on the camp of Calais. Viola, Elodie Gaudet. Viola da gamba, Louis Michel Marion.

A series of visual and sound studies also exists:

ERASURE 05:00

Voice/Mixt-violin.

https://vimeo.com/264612719 code TRAGEN.HZ

Based on a lyrical singing improvisation, ERASURE is the instrumental and vocal opening of the project. Sections of screeching sequences alternate, wear down and alter the envelope of voices like those who tried to cross the barbed wire border known as “razor blades” that borders the entrance to the railroad tracks of the Channel Tunnel. ERASURE, the English word at the limit of the French whispers the razor edge and the scratch on the map.

NOMANSLAND 07:30

Viola/Baroque bow.

With displacement of the instrumentalist on the stage.

https://vimeo.com/264613883 code TRAGEN.HZ

Bordered by an expressway, a dried-out land of overexposed sand, trodden by the suspended footsteps of waiting men. A wandering and slowed down walk, in a situation of being crushed on a ground to be crossed. From bow’s pulsations iterative sounds, to the hindrance of waiting, the harmonics pierce, draw, sharpen or sign the wind’s environment.

NIGHT SHOT 04:35

Viola da gamba/Theorbo/Fieldrecording

https://vimeo.com/264732345 code TRAGEN.HZ

A hole made of images where a void sizzles. A swarm of pixel dust, the “under-ex” falling scrap image… The effigy or the stele of a woman from behind and the pulsations extricated from the theorbo turn the acoustic space upside down in order to convey the fire at night.

SO LONG 03:10

Viola da gamba/Theorbo/Fieldrecording

https://vimeo.com/264614397 code TRAGEN.HZ

The image’s flickering, its sizzling, tips over into a kind of hoarse voice; the hail, the grail of the viola da gamba mingles with the inflections and complexions of the voice of a young teenager coming out of his shelter.

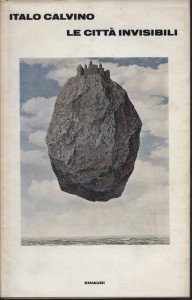

3. The Images

Series of images extracted from the visual and sound study of SYNAPTé:

SYNAPTé (07:40):

Based on a vocal improvisation inspired by mourning songs and notations of ancient tragedies – synapté – meaning litany in ancient Greek, this video/visual and sound study of the project TRAGEN.HZ serves as a kind of matrix. The voice, rough, a moan, stretches and is diffracted: the dismantling of life communities in the camp. Voice as if withdrawn from the precarious living conditions of burnt wood, lonely, it raises in a bit of hot ashes what remains of waiting in passing silhouettes. Moaning of the oracle, lament in search of consolation, primal and altered voice, voice of the evidence that erases and recollects and restores these images as a witness of this long history of migration and war.

Plus forts

Plus forts