Accéder à la traduction en français :

Français

INTER MUROS

A deconstructive approach to performance practice in John Cage’s Four⁶, focusing on undecidability, viral interpenetration and the merging of domains.

Clare Lesser

Summary

Murus

John Cage – Four⁶

Four⁶ – ART: Abu Dhabi, April, 2018

Pharmakoi

…begin and end at particuLar/points in timE…

Murus

Murus, maceria, moerus, mauer, mur…

Immured, mural, rim….

…cell wall, prison wall, curtain wall, city wall…

…retaining wall, harbour wall, dividing wall, connecting wall…

…enclosure, partition, screen, divider, party wall, panel, bulkhead…

…shelter, guard, garden wall, dam, fortification…

…load-bearing wall, decorative skin, Four Walls…

…off the wall…

…mûre, mûr…

…undermining…

…with/out foundations…

Complicated things walls, and if we step into this stream of thought, who knows where we’ll end up? Maybe we’ll be washed off our feet and land on our heads…or crash into a wall?

Rather than immediately breaking down any walls, consider what it could mean, instead, to be between or within walls, to question them, to pick at the mortar, to make their foundations tremble a little, perhaps. But how to go about this process? Deconstruction seems a good place to start; examining the joins, quoins…penetrating the fabric, initiating the process of interrogation, of weakening, of the ‘perhaps’. So, let’s attempt to open our eyes and ears to the unfolding of deconstruction within and across domains, drawn from the work of Jacques Derrida and Bernard Tschumi (I could equally bring in Simon Hantaï and Valerio Adami), focusing on two main areas of concern: the pharmakon (and undecidability) and the virus.

There are a number of apparent contradictions or oppositions in the opening list (shelter/prison, connecting wall/dividing wall, load-bearing wall/decorative skin). Walls can seemingly occupy two or more apparently opposing states simultaneously, and as such, could be seen as pharmakoi. So, let’s consider a work of ‘music’ where these walls, these pharmakoi, these possibilities for foundation shaking and boundary dissolving, these apparent contradictions and blurred edges, these instances of aporia (or perplexity), are integral to the performance, and where the performer/creator (the ‘wild card’) can strive to deconstruct, or push, the ‘rules’ (walls) of the ‘game’ to breaking point.

John Cage – Four⁶

Four⁶ (1992) for four performers, rather than ‘musicians’ or ‘players’ specifically, or rather, it is for four ‘performers’ on the front cover and four ‘players’ on the parts (does this play at games, at the theatre, does it play with play?) is one of John Cage’s time-bracket works, so named because during performance each player should

Play within the flexible time brackets given. When the time brackets are connected by a diagonal line they are relatively close together. (Cage 1992, p2)

Thus, player one opens with:

0’00” ↔ 1’15” 0’55” ↔ 2’05”

2

Cage also gives us two pieces of information about the types of sound he has in mind, I should mention here that there is no given ‘filling’ for the time brackets, that is for the performers to provide, because the work is

for any way of producing sounds (vocalization, singing, playing an instrument or instruments, electronics, etc.) … (Cage 1992, p1)

And Cage further tells us to

Choose twelve different sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude, overtone structure, etc.) (Cage 1992, p2)

So, within the walls of the ‘rules’, within the boundaries of the work, we have creative contradictions or opportunities in the work from the outset. Cage offers us a less obvious pharmakon in that the sounds are apparently both fixed and free. We assume that Cage intended that each of the twelve sounds should have fixed characteristics, but why the first sentence in that case? It is redundant, it opens up the possibility of aporia. Why not just say ‘produce twelve sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude etc.)’? That would make perfect sense to a musician.

He also gives the performers complete agency regarding where, i.e. from what domain (if any), they come[1], as well as a certain amount of flexibility within the overall ‘structure’, in-as-much as the time brackets (containing walls) allow for variability in start and stop times for each ‘event’. Those time brackets are empty shells of course – waiting to be filled, waiting to be inhabited by events (what Derrida calls ‘the emergence of a disparate multiplicity’ [Tschumi 1996, p257]). In other words, their ‘programme’ is unfixed. The composer/performer relationship or hierarchy is completely unsettled (another pharmakon), for who is actually ‘composing’ the performance here: composer, performer(s), both, neither? Oh yes, and there’s no ‘master’ score either, only parts. Each player is independent, in a sense walled off from the others…perhaps?

Could the pharmakon be useful in overcoming boundaries, changing (challenging) the wall’s structure and function? If a binary opposition (included/excluded, free/trapped, etc.) can be overturned, i.e. have its function cast into doubt, then walls can become thresholds, conduits, zones of connectivity, not barriers. The pharmakon is one of the key concepts to be found in Plato’s Phaedrus, so let’s consider Derrida’s explication of the pharmakon, as found in Dissemination, “Plato’s Pharmacy”.

This pharmakon, this “medicine”, this philtre, which acts as both remedy and poison… (Derrida 2004, p75)

and

This charm, this spellbinding virtue, this power of fascination, can be – alternately or simultaneously – beneficent or maleficent. (Derrida 2004, p75)

and

If the pharmakon is “ambivalent”, it is because it constitutes the medium in which opposites are opposed, the movement and the play that links them among themselves, reverses them or makes one side cross over into the other (soul/body, good/evil, inside/outside, memory/forgetfulness, speech/writing, etc.). (Derrida 2004, p130)

So, the pharmakon is a space where oppositions can be overturned; a passage or movement of conjoining and interpenetration, the either/or, neither/nor, the ‘and’. The overturning of oppositions is not solely confined to speech and writing (although that is what Derrida is referring to here): it is equally relevant to other fields, e.g. architecture, the field par excellence of walls, the bastion of apparent solidity and structure, and yet also an important area of collaboration for Derrida with Peter Eisenmann and Bernard Tschumi during the 1980s[2]. Derrida was somewhat dubious about such a collaboration initially, telling Tschumi “But how could an architect be interested in deconstruction? After all, deconstruction is anti-form, anti-hierarchy, anti-structure, the opposite of all that architecture stands for.” ‘“Precisely for this reason,” I replied.’ (Tschumi 1996, p250). Tschumi also remarks that deconstructive strategies in architecture were developing momentum throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, when architects began to

…confront the binary oppositions of traditional architecture: namely, form versus function, or abstraction versus figuration. However, they also wanted to challenge the implied hierarchies hidden in these dualities, such as “form follows function” and “ornament is subservient to structure”. (Tschumi 1996, p251)

And Tschumi’s ‘radical’ pedagogical practice at the Architectural Association and at Princeton in the mid-1970s exploited the merging of domains (e.g. architecture and literature) from the outset:

I would give my students texts by Kafka, Calvino, Hegel, Poe, Joyce and other authors as programs for architectural projects. The point grid of Joyce’s Garden (1977)…done with my AA students at the time as an architectural project based on Finnegan’s Wake, was consciously re-used as the organising strategy for the Parc de la Villette five years later. (Tschumi, 1997, p125)

So Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette project (1982-98), the redesign and development of a large urban space (the former abattoir complex in north-eastern Paris), exploited cross-programming, a reappraisal of the ‘event’, the play of the ‘trace’, and various other deconstructive strategies in its composition of lines, points and surfaces. It is probably best known for Tschumi’s iconic bright red folies (multi-programme or programme-less structures within the park): one of the folies could be either a restaurant or a music venue, neither a restaurant nor a music venue, or, a restaurant and a music venue. So, the folies are pharmakoi, they are undecidable; they reject the ‘walls’, the containment, of pre-determined ‘programme’. They are empty shells – time brackets.

How does this plurality of undecidables play out in Four⁶? What is undecidable in the work, and what implications might this have for overturning walls in pedagogy and praxis? To explore further, let’s turn to a recent performance of Four⁶ which I instigated.

A partial list of the undecidables in Four⁶ could include:

- Forces – who can perform the work?

- Content – what will inhabit the time brackets?

- Hierarchy – who is the composer?

- Score – who is in control?

Four⁶ – ART: Abu Dhabi, April, 2018

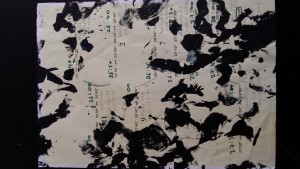

The art version was conceived as a way of stepping away from music, while still acknowledging its trace within the work (figure 1). Each performer was asked to individually design twelve art related actions. Time bracket execution could be either pre-planned and notated on the score, or chosen/performed ‘live’. I asked the performers to interpret ‘art’ in any way they liked, which resulted in a mixture of performance art, sound art, fine art, theatre, performance-poetry, etc; and I also asked the performers to devise their ‘events’ in isolation, so that the live performance would be unrehearsed and all reactions would be spontaneous, potentially surprising to executors, co-performers, and the audience ̶ (a nod towards Cage’s definition of the ‘experimental action’ as ‘one the outcome of which is not foreseen’, Cage, 1961, p39).

A 6X3 foot canvas sheet was used, mounted on a wooden frame and supported on blocks (to allow space for cutting) on a large table. The following items were available to all the performers to use if they so chose: tubes of paint (acrylic) in white, black and blue, tubs of paint in the same colours, chalk, charcoal, knives, glasses of water, glass bottles, pencils, screw drivers, paint brushes (varied sizes), knife sharpeners (steel), rags (for erasing/painting, etc.,). One performer also brought a light -sabre to paint with. Performers were free to use any part of the body during the work’s realisation. The choices made by players 2 and 3 were:

Player 2 – Sounds (Actions)Speak,

1. Speak, 2. Pencil, 3. Overpaint, 4. Wood blocks, 5. White, 6. Knife, 7. Black, 8. Screwdriver, 9. Blue, 10. Silence, 11. Sing, 12. Cough.

Player 3 – Sounds (Actions)

1. Tacet, 2. Shred score & add to canvas, 3. Rattle brushes, 4. Splatter with brush, 5. Paint tube thrown squirt, 6. Charcoal writing, 7. Water splatter, 8. Bottle & jar percussion, 9. Erase, 10. Knife sharpen, 11. Shove other performers, 12. Slash canvas.

Figure 1: portion of the canvas immediately after the performance (April 2018),

showing wet paint and shredded performance part (centre).

Pharmakoi

The first pharmakon concerns the forces involved: who can perform this work? Does the work have walls that prevent participation and access? No, the boundaries of performance are very open. In other words, anyone can perform Four⁶; no classical or formal music training from any tradition is required. Four⁶ is music and is not music; it will accommodate performers from any artistic domain, from anywhere in fact, who are perfectly at liberty to stay within their own domain (although these domains will bleed into one another): artists, musicians, scientists, actors, historians, philosophers, vets…the list goes on. The wall regarding discipline ̶ the ‘who?’ is the work for ̶ is unstable and weakened; the performance can be a hybrid, a mixture of domains, a two (or four) way viral infection in every moment of performance. There are social and political implications here; there are no barriers (walls) to access, no hierarchy, and no pedagogical foregrounding is required.

If the players can come from anywhere, any domain, then the ‘content’ or ‘programme’ of the time brackets will be equally open. That is: the programme does not have to be ‘music’. The version I have outlined above has a rough focus, but no ‘theme’ is actually necessary, it is a container for events to take place in. The performers were drawn from the fields of music, visual arts, psychology, and classical Arabic, so we have a work that is music and is not music. The time brackets are like Tschumi’s programme-less folies, described by Derrida as ‘a writing of space, a mode of spacing which makes a place for the event’ (Tschumi, 2014, p115). The folies have a number of shared traits with the time brackets: a time bracket is a mode of spacing in time, and it can be filled with anything, with any ‘event’ that creates sound, drawn from each player’s lexicon of twelve, just like a folie has an undefined and open ‘programme’ with a variable lexicon of possible events[3]. The combination of the time-bracket events (programmes) allows the individual domains to merge, to infect, to overwrite, to hybridise, like our earlier example of a folie, which interbred a performance space and restaurant. In the ‘art’ version, the domains of music, art, theatre and philosophy all occupy the same time space.

Events have afterlives too, cinders, if you like. As the canvas dries out, the art version continues to change long after the performance is finished; it is not confined within those 30-minute temporal ‘walls’. It continues to evolve through changes of colour and texture (figure 2). The drying process both reveals and conceals writing (on the canvas and the additional shreds of the parts) and the modes of application and addition (charcoal pieces below). As the paint cracks and falls off, yet more traces of the performance’s own history appear, while the pages of the individual parts can become art objects in their own right (figure 3): an archaeology of performance. The cinders are carried along in the flux.

Figure 2: portion of the canvas one month after the performance (May 2018),

showing changes of colour and texture,

small shreds of parts (bottom left) and charcoal (centre right).

Figure 3: player 4, part with paint additions

acquired during the 30 minutes of ‘performance’.

…begin and end at particuLar/points in timE…[4]

Cage explains variable structure very succinctly, in the form of a mesostic:

These time-brackets / are Used / in paRts / parts for which thEre is no score no fixed relationship / … / music the parts of which can moVe with respect to / eAch / otheR / It is not entirely / structurAl / But it is at the same time not / entireLy / frEe (Cage, 1993, p35-6).

Note that Cage says the ‘parts of which can move with respect to each other’ (my italic), not that they must or should. And what could respect mean here? Literally that they respect each other’s space, each other’s boundaries (walls), that they do not interfere, overwrite, erase, infect or cross-programme; or the opposite, that they can move because the others allow free passage, permit themselves to be infected, erased, grafted, hybridised or overwritten, that they allow interpenetration because there is ‘no score, no fixed relationship’, no controlling hand?[5] Again, the wall is weakened, it’s function is heterogeneous, open to change, but its trace, its ghost, is still there.

If there is no score, only parts in a timed dance drawn from a variable lexicon of forty-eight moves, then who is the composer? Who has overall control? Who holds the key that allows passage through the walls (if they exist) of this work’s creation, of its direction? It is another pharmakon; John Cage is the acknowledged author (his name is on the front cover), but is he really the author, the author of the content? We only have parts, no score, and our parts have no substance; as yet they are unformed, except in terms of variable lengths and their order, e.g. player 1 starts with sound event 2. It’s like a drama without a unified script, with characters who do not know their relationships to the other characters (back to actions with unforeseen outcomes), and dialogue that is both secret and disordered. In Four⁶ we have ‘stage directions’ (instructions), and we have a variable temporal ‘choreography’ which tells us approximately when to put the things that we, as performers, have found. But wait a minute, aren’t the fillings of the time brackets ours? We found them, after all, we devised the sounds, and we decided precisely when and where we were going to put them, we decided that sound event 12 was going to be coughing or canvas slashing and we decided when we were going to cough or slash the canvas within that time bracket – so perhaps it would be better to say that John Cage is an author of Four⁶ rather than John Cage is the author of Four⁶?

So, the hierarchy is undecided, there is no single controlling presence in the performance, there is no ‘master’score. The performers have a very considerable amount of agency as long as they play by the ‘rules’ (for Cage was never one for a free-for-all). Even so, it’s a very generous and egalitarian way of composing, always remembering that rules can be outmanoeuvred (whilst still remaining within them), interpreted in new ways[6]. All those hierarchical ‘walls’ that can block (or at least make it one way only) the passage of communication between performer and composer are open; the walls are porous (are they even walls anymore?), so neither the composer/performer interface nor the performer/performer interface is fixed. In the art version, the audience/performer interface is also more open – paint can fly everywhere. The performer is a composer/performer hybrid interpreting within a composition, composing within an interpretation; the composer (Cage) has opened himself up to the viral communication of the performer; the performers have opened themselves up to independent/not independent forms of grafted praxis; all interact while retaining their individuality, all can overwrite each other’s work (in sound and/or paint), all can graft gesture and expression, opening themselves to the virus, conversing in many ‘languages’ across domains, allowing themselves to be penetrated at a quasi-cellular level.

As Derrida says

…all I have done, to summarize it very reductively, is dominated by the thought of a virus, what could be called a parasitology, a virology, the virus being many things…The virus is in part a parasite that destroys, that introduces disorder into communication. Even from the biological standpoint, this is what happens with a virus; it derails a mechanism of the communicational type, its coding and decoding (Brunette and Wills, 1994, p12)

The virus unsettles things, makes them tremble, and shakes them up, disorders communication (messages get lost or ‘wrongly’ delivered, they are open to a multiplicity of interpretations), makes a space for unpredictable interventions, introduces aporia. In Four⁶ we can see the evidence of this virus through its trace, the way it leaves marks (imprints) behind in the dust, in the ashes (charcoal), in the paint, in the sound. So we have a viral melding of actions in performance (altering another’s actions which leaves a mark), of ‘persons’ (performers/audience/composer), and domains (art/music/theatre, etc.): in the art version of Four⁶,art, music and dance are all present, as is theatre[7].

The virus infects the moments when the the surface of the canvas is created, when colours blend to become new colours, are overwritten, are grafted, are erased; it leaves its mark through the accretion and revealing of layers, through writing and overwriting, through deconstruction as the knife slashes through the surface, exposing the underside of the canvas which in turn becomes a new surface, through the intentional alteration of another player’s ‘event’ by physical interventions – shoving, scrubbing, cutting and covering. So, Derrida’s parasite destroys (or should one say it ‘fixes’?); but it only destroys a moment’s possibility, an eye-blink of the painting’s ‘history’ (of this performance’s canvas). It forces a change, a mutation, and who knows where that will lead?

There are other traces in the ashes too; ‘il y a là cendre’ (Derrida, 2014, p3), intertextual traces, hypertextual traces, of other works (in multiple senses: the current canvas’ own history, its possible history that could have been, the history that is yet to come, and the histories of the domains to which it now aligns itself). The lexicon of 48 sound events is a net of traces; of the Greco-Roman muralists, of baroque religious painted interiors (whose collective endeavour will always raise questions of authorship[8]), of Fontana, Kiefer, and Hantaï, the Situationists, Vienna Action Art, early Fluxus, Heiner Goebbels, Robert Wilson, Heiner Müller, the traces of post-dramatic theatre, of the dance-theatre of Lindsay Kemp, and other works by Cage of course. These traces refer to other traces, in chains of infinite resonance. The traces of our own experiences will always be present in any endeavour as well – how could they not be? Walls are omnipresent, for good, for ill, make of them what you will, but they are not merely barriers. Perhaps it is better to acknowledge their functional heterogeneity than to attempt to break them; to strive for weakened versions (as nets), to allow their transfiguration, to embrace their undecidability, for then walls can be barely perceptible, almost transparent, they can be s[wall]owed.

1. This is equally applicable to the sounds themselves.

2. Cage found a new appreciation for the city and new ways of looking at its constructions, its traces, its interactions, after taking a walk through Seattle with the painter Mark Tobey. (Cage & Charles, 1981, p158)

3. In one sense they could be considered heterotopias.

4. Cage, 1993, p34.

5. Derrida’s use of ‘Animadversions’ in texts such as Glas, Cinders and Tympan (Margins of Philosophy) are another way of looking at the presentation of, and commentary (sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit, sometimes silent) on, simultaneous, parallel and sequential actions across the same surface, i.e. the canvas.

6. As Cage said: ‘We are not free. We live in a partitioned society. We certainly must take those partitionings into consideration. But why repeat them?’ (Cage & Charles, 1981, p90)

7. Regarding theatre, one of my co-performers almost cut the canvas in half at one point during the performance, and I was quite shocked – wondering if there was both enough surface left to work on, and whether the whole thing would unravel-, but on the other hand, I thought it was very funny and had to stifle my desire to laugh for the rest of the performance, and that brings another trace into play, that of the theatre’s tradition of making co-performers ‘corpse’.

8. As early as 1934 Cage found the group endeavour of what he termed medieval or gothic art appealing. (Kostelanetz, 1993, p.16)

References

Brunette, P., & Wills, D., Deconstruction and the Visual Arts: Art, Media, Architecture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Cage, J., Silence, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

Cage, J., Four⁶, New York, NY: Edition Peters, 1992.

Cage, J., Counterpoint (1934) in Kostelanetz, R. (ed), Writings about John Cage, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1993.

Cage, J., Composition in Retrospect, Cambridge, MA: Exact Change, 1993.

Cage, J., & Charles, D., For the Birds, New York, NY: Marion Boyars, 1981.

Derrida, J., ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’ in Dissemination, trans. B. Johnson, London: Continuum, 2004.

Derrida, J., Cinders, trans N. Lukacher, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Derrida, J., ‘Points de Folie – Maintenant l’architecture’ in Tschumi, B., Tschumi Park De La Villette, London: Artifice Books, 2014.

Kostelanetz, R. (ed), Writings about John Cage, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1993.

Tschumi, B. Architecture and Disjunction, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

Tschumi, B., ‘Introduction’, in J. Kipnis and T. Leeser (eds.), Chora L Works, New York: Monacelli Press, 1997.

Tschumi, B., Tschumi Park De La Villette, London: Artifice Books, 2014.