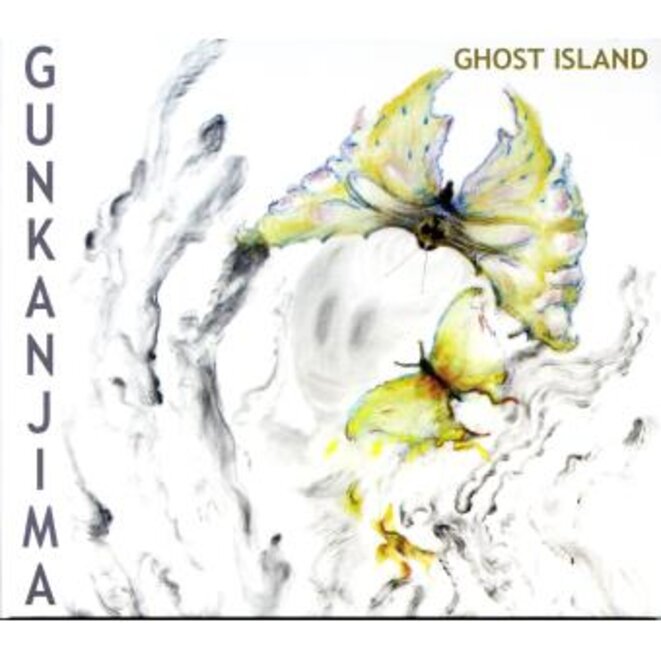

Ghost Island

Noémi Lefebvre

(from her blog médiapart)

Gunkanjima is a place, a ghost island, a warship, an accumulation of buildings, an urban system, concrete composition, a mining town, an energy era, a geological hole, some pure coal called diamond. It is a switched-off function, a cemetery of objects, beds, tables, TVs, radios, calculating machines, sewing machines, typewriters, toys, curtains, fans, shoes, papers, bowls, sinks, fallen roofs, broken window panes, bird calls, rubble, a telluric city in the middle of the sea, outpost of chaos, nature after man, a silent place from where music begins.

Gunkanjima is a musical place of research and creation, an open construct, a sound fabric, an ensemble associating timbres, some broken up language, ancient poetry, bruitism, onomatopoeia, animal-human song and screaming, organism and machine, a territory of invention situated in this post-industrial time and in this globalized space where we have to live. This ensemble of six musicians demonstrates that research and creation are not two separated domains, but that they are as indispensable one to another as are work and play, memory and forgetfulness, knowledge and uncertainty, intention and invention.

This music of the present, in the making, obliges us to break with habits and classifications in trends, aesthetics, genres, cultural influences, to refuse decidedly any identification to already known consensual frameworks, which tend to place the artists in front of a paradox: one should invent in continuity, look for ideas without crossing the prescribed limits, create something new following the line, without getting out of the context organized by designations, as if these designations were here to stay for ever, whereas they appeared themselves at a given moment in order to burst other paradigms apart, define something that the old classifications were unable to grasp.

We may try to situate Gunjanjima in a trend: rock without a doubt, free evidently, electroacoustic indisputably, contemporary music absolutely!

At the same time no; it would be equally inappropriate to say that this creation is under European or Japanese influence, from somewhere or from nowhere, best not to look for a provenance or an affiliation, we have even to renounce discovering a multicultural origin in hearing it, or an expression of “world music”. The origin of Gunkanjima is not somewhere, here, elsewhere or everywhere: its origin is a project, and the origin of the project a desire for a shared project by musicians who bring to it their personality, their energy and their imaginary.

The habits of classifying, in which overlap the modes of acknowledgement of socio-musical spaces, the organizations of distribution networks, the formalizations of musical criticism, the commercial rationales, tend to be prolonged in listening criteria and to prescribe a sort of attention displacement on to categories. Do they necessarily discard the possibility to hear what is being played? It does not matter if our listening is informed by a history of representations, by an acculturation or by education, because even if we have evidently some sound references, there is a moment in which experience cannot rely on experience, a moment in which what we hear is awaking clear audible understanding, is disconnecting knowledge from erudition, awareness from boredom, listening from memory, perception from prejudgments, acculturation from cultural history. This moment is what Gunkanjima realizes.

But how?

Hashima was a black rock island off Nagasaki, where the first big concrete apartment complexes in Japan were built for a population that came to work at the exploitation of coal. This island, progressively enlarged to reach 480 meters long by 160 wide, overcrowded, transformed into “Gunkanjima”, “warship” in Japanese, for the intensive coal exploitation by Mitsubishi, was never conceived according to a general plan of urban development. The buildings were gradually added, as the mining activity intensified, until it was decided, in 1974, to close the mine and that all the inhabitants should leave the island within a few weeks. Nevertheless, all these buildings, impressive by their height and imbrication, are linked to each other through several levels and form a mega-structure and some circulations, which integrate some public spaces, aisles, terraces, a main square “Ginza Hashima”, as if there could have been an initial urban design.

Of course, this mode of urban construction is not specific to the Hashima island. Most towns, described a posteriori as extremely complex and coherent organisms, can display ingenuity of general structure and of circulation nevertheless invisible to those who built it. But the ghost-towns reveal it better than others: it seems that the cessation of all activities and the disappearance of any human presence render possible an organic analysis coldly after the fact. Sometimes the dead bodies have to be observed in order to understand the living ones.

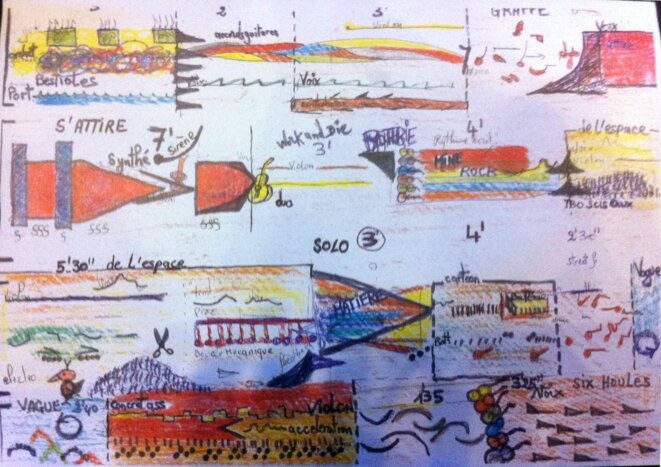

To observe coldly after the fact the music of Gunkanjima is not possible: even if it is burned on a CD, it is not fixed! For the concert is not the public restitution of the recorded work; instead, through the gathering of musicians in rehearsals and on stage, at each performance, Gunkanjima is created and recreated. Therefore the musicological analysis of a “musical text” defined once and for all would most probably not be able to seize the creative energy, which determines its strength and its form, in the first place because there is no text, and then because this non existent text is constantly modified. The graphic scores created for Gunkanjima have a musical function inscribed in play. In this passage, for example, called the space, in which the musical idea of a “living space but with almost nothing” is developed, the graphic score is used foremost as a reminder of what, in improvisation and in the proposed ideas, will serve as benchmark or as thread, from which is developed a freedom of play. Everything is constructed, nothing is determined in advance.

No way to relate the realization to a prior idea, no certainty, no prediction, and nevertheless there is a circulation, an ensemble of networks. The musical elaborations of Gunkanjima are elaborated little by little, in a common research, with some materials, chosen constraints and a lot of imagination. These music pieces have their specific form and their own matter, and little by little, these pieces connect in a pathway. As the musician guitarist Gilles Laval says concerning the initial creation of the group: “we arrive somewhere, we come out again, then it continues, we don’t know where it leads, I like this idea of some cooking that is grasped at a given moment, it opens and it closes, and in fact, the cooking continues, it still leaves some traces”. As in the case of the island, of which the human history, linked to the intensive coal exploitation, does not constitute a whole as such outside history, in Gunkanjima there is no beginning nor ending, but a living, poetic and violent moment, fugitive with regard to the thousand years of necessary sedimentations to transform the vegetal and organic debris into coal, a human time in a long history without humans, which as such lets itself be grasped, immediately, as soon as it begins, this is why, in concert as in CD form, the pieces are not pieces.

It is possible to listen to an isolated track of the CD, but in reality the music is made up by a single continuous piece; “I cannot imagine that the piece could be stopped at some moment, and then to start again; for me it is a single piece from beginning to end, there are things happening, and then in the same way I started off from this story, from this island, and then I could not see how to divide this town into fragments of town”, explains Gilles Laval.

The vitality of this ensemble lies in the rapprochement of personalities whose musical worlds are already present. “When I gathered together this group, I knew that they were individualities. Each person is able to develop her/his projects alone”. The equilibrium is found in co-construction, in which whoever pretends to be the leader [chef] is nothing more than a liar [menteur]: “each person is at his/her place and the detail is discussed more and more. These are musical discussions in the course of elaborating propositions, each one speaks and may intervene. The decisions are always based on common choices”.

Gunkanjima, the island, is not a distant theme, exotic pretext to make music, it is constitutive of its architecture. It is not a stylistic subject, an allegory, a theme from the past, this is why there is no point in looking for Japanizing references or anything that is overplaying Japanese music. If there is something of Japan in this music, it is because three out of the six musicians are Japanese. The time is creation or is nothing at all.

See also the blog chronicle of June 20, 2015.