Access to Guide to the Fourth Edition 2025 Edition and List of Contributors to the Fourth Edition

Access to the original French text of the Editorial 2025

Éditorial 2025

Artistic Research: Reports on Practices

Fourth Edition – PaaLabRes

Summary :

Introduction

To Document Practices and Informal Research

Practices

Report, Inquiry, Research

The contributions

PaaLabRes Fourth Edition, Future Contributions

Introduction

PaaLabRes (Pratiques Artistiques en Actes, LAboratoire de REchercheS) [Artistic Practices in Acts, Research Laboratory] is a collective of artists, in existence in Lyon since 2011, which attempts to define the outlines of research carried out by the practitioners themselves concerning artistic expressions that do not result in definitive art works.

PaaLabRes aims to bring together, through action, reflection and research, diverse practices that cannot be closely identified with the frozen forms of patrimonial heritage, nor in those imposed by cultural industries. These practices often involve collective creation, improvisation, collaboration between artistic domains, but without creating an identity that excludes other interactive forms of production. They tend to call into question the notion of autonomy of art in relation to society, and they are grounded in everyday life, and in contexts that mix art with sociology, politics, philosophy and the logic of transmission and education. As a result, these practices remain unstable and ever-changing, they are truly nomadic and transversal.

To Document Practices and Informal Research

The fourth edition of the paalabres.org website is linked to two concerns. On the one hand, there is the question of how to document the profusion of practices that most often take place anonymously. On the other hand, we attempt to show that within these practices, silent research approaches are at work, often unbeknownst to the people involved. Artistic research, thought of as directly linked to the processes of elaboration of practices, to the definition of projects, to interactions between people participating in them and eventually to particular modes of documentation in use (see the stations « Débat » et « Artistic Turn » in the first edition of paalabres.org).

The extraordinary diversity of the practices calls into question the notion of universalism and strongly challenges the hegemony of certain practices. Such diversity creates the necessity to include within the production mechanisms of elaboration that are related to bricolage, experimentation, and research. It is no longer simply a question of the conception of materials at the heart of artistic acts, but of including a more global approach concerning the interactions between individuals, the methods being considered, the different ways and contents of transmission and learning, the relationship with institutions, etc. To be able to find one’s way through the maze of the ecology of practices, of this proliferation of often antagonistic activities, there is a need to develop specific reflective tools. First, it is necessary to describe the practices in all their aspects and to question them in order to bring out their distinctive problematics. An inventory seems necessary in the form of narratives describing in detail what happens during a given project, in the documentation of practices using various media and in the formalization of concepts inherent to practical acts in the given context, notably concerning the unstable relations between intentions, daily reality, the final realization of productions and their public dissemination.

Artists often do not have the time or show little interest in narrating the details of their practice, in documenting processes for critical reflection. Often the artists wish that the attention be focused only on their finished productions and not on the behind the scenes of their elaboration. The explanations are considered too academic and not doing justice to the uniqueness of artistic approaches, or it is considered that art should keep its autonomy and

remain detached from the prosaic world.

Behind-the-scenes of research is largely ignored in the content of its publications (articles, books, conference presentations, etc.). The presentation of results takes precedence over the trial and error that preceded them. Yet research is full of starting up processes, unstable elaborations, and provisional documents. For example, the journal Agencements, Recherches et pratiques sociales en expérimentation has a section called « coulisse(s) » (behind-the-scenes) designed to “provide readers with major research writing, which remains confined in the workshop area where each one works or in the backstage of research” [Bodineau&co, 2018, p.9].

Concerning artistic practices, one of the risks is to leave the exclusivity of the explanations to the external viewpoints. In order to overcome the obstacles encountered by the protagonists of the practices, PaaLabRes proposes collective processes to finalize the contributions by putting in interrelation diverse skills. Thus, the narration of an artistic project can be clarified in an interview, in particular to help identify the points left obscure; oral expression is in this case easier but implies intelligent transcription skills. Documentation methods are often highly technical in relation to the various media and require collaboration. In this context, technical skills must be extended beyond their specialization and definitely include the ability to understand the issues at hand as perceived by those directly involved in the development of practices.

Critical analysis of practices is generally considered to be expressed in a written text, informed by references to previously published works on relevant topics. In the case of artistic research, this requirement is not necessarily what best suits the subversive character of certain artistic approaches. But the invention of textual or other technological devices appropriate to the spirit of an artistic project still seems to be insufficiently explored and remains a delicate proposition. How to consider handling both the concepts in all their complexity and their presentation remaining faithful to the intended artistic approach? How to expose at the same time the aesthetic points of view and to put them in question?

Narration, documentation and questioning of practices are by nature multifaceted: they involve events (performances, public presentations, workshops, conferences, etc.), multiple media (written texts, scores, graphics, videos, audio recordings, images, words), and numerous mediations that are constantly part of complex interaction processes.

The use of the term “artistic research” in the context of the fourth edition should therefore not be limited to what is precisely formalized in higher education and research institutions. It should be remembered that many artistic practices may contain phases of experimentation and processes that can be described as “informal research”. The project of the PaaLabRes collective is to put into relation the antagonisms that historically exist between artistic practices and university research on the one hand, and between artistic practices and the sector in charge of teaching these practices on the other. Moreover, the comparison of artistic practices with practices in use in fields that have special resonances with the arts (such as sociology, anthropology, linguistics…) can be very useful for the elaboration of a more general reflection on today’s cultural contexts. Therefore, the call for contributions for the fourth edition remains very broad and concerns the realms of university research, arts education, and the diversity of practices in the field of the arts and other related disciplines.

The objective of the fourth edition is to develop a database of practices, more or less ephemeral, which constitute the horizon of today’s culture. The aim is not to propose models that can be developed into methods with guaranteed standardized results, but rather to have access to references from which one can draw inspiration and compare procedures. For this reason, the fourth edition is not limited in time, but will remain open until the moment when it seems that there is too much information. Anybody can at any time propose a contribution to this fourth edition.

Practices

The acts of practice are inscribed in time, one after the other, without giving the possibility of a panoptic view at the moment of their accomplishment. While doing, to reflect on all the elements at play is difficult, and it is only in retrospect that actions can be evaluated. Decisions during practice are rapidly made or even in an immediate manner, they can at any time result in changing direction, but without taking the time to really measure the consequences [See Bourdieu, 1980].

In the language succession, the meaning of a word can be changed by the succession of other grammatical elements, but at the time it is spoken, it carries a meaning perceived unilaterally. It can also offer openings towards the multitude of meanings it could produce. The same phenomenon tends to be manifested in the act of doing something. This act may change meaning according to acts that will follow, but at the time of doing, the individual who accomplishes it can only concentrate on what makes sense at this precise moment in this particular act.

This leads to the question of how to approach practices in the field of research? The temporal nature of practices means that we need to seriously consider processes into which the actions in progress evolve as they confront contexts. Nicolas Sidoroff [2024] defines practices as follows:

Procedures in a context.

With institutional dimensions.

And that lead beyond relationships between individuals.

Institutional dimensions are part of the context, but it’s often necessary to make them explicit so as to not forget and to be able to signify what they intersect with. This is one of the five dimensions proposed by Jacques Ardoino [1999] to describe human interactions as accurately as possible.[1] This dimension is worked on by so-called “institutional” approaches (psychotherapy, pedagogy, institutional analysis). This dimension is multifaceted, it brings together values, norms, social beliefs, ideological and cultural models, the histories in which we are all enmeshed, the imaginary, ghosts (absent persons but who have influences on the activity in process), and so on. Moreover, practices go beyond

social relationships between individuals alone to play a part in transforming social relations (according to Danièle Kergoat). Practices develop in a reciprocal movement. They are driven by a subject who is a “collective producer of meaning and actor of his or her own history” [Daniel Kergoat, 2009, p. 114], and they enable at the same time such subject to become collective producer and actor. [Nicolas Sidoroff, 2024, p. 156]

And finally, in the framework of this PaaLabRes edition, to consider practices as procedures in context and as succession of acts, leads to the possibility of narrating them. Practices can be recounted: this is what happened, or rather, better still, what somebody did,[2] in the present tense of the action, to be as close to it as possible. Someone does, we do, I do. Then, writing in the broadest sense of the term, what we call “documenting”, can take place, and with it, research on artistic fabrications and constructs.

The actions in progress implied in the active verb of “musicking” are univocal yet multiple acts [see Christopher Small, 1998]: they unfold in time, they last, they are not isolated, and they must constantly confront contexts that change as quickly as the weather. At the time of making a decision to carry an act, thinking is immediate. Everything is determined both by the actors’ past (habits, acquired knowledge) and by the situation to be faced (in the presence of other people and particular environments). The act can then be frozen in a conventional stage, if you don’t have the means to break away from the obsession with doing things right. But the time that follows the decision can also be viewed as a pathway to follow (to wander) in which unforeseen events may emerge opening up new options: the notions of trial and error, tinkering, experimentation and research then assume their full meaning.

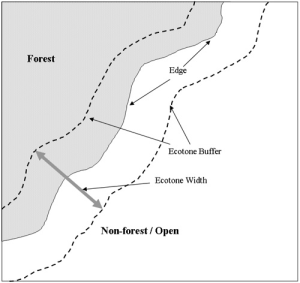

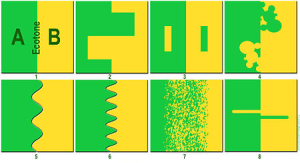

Actions in progress are situated [Haraway, 2007], but they are also multiple, giving rise to a multitude of often contradictory injunctions. As a result, they are always inscribed at the edges, fringes or margins, placed in between “nuclei” that Nicolas Sidoroff defines in the context of his own practices as “performance, creation, mediation-teaching-learning, research, administration, and technique-instrument building.” (See Lisières, 3rd Edition PaaLabRes). Each act is situated with a different intensity in each of these nuclei that make edges exist and living in such ecosystems. Potentially, each act is largely within a single nucleus, but is also in interaction with all the others.

In Fernand Oury and Françoise Thébaudin’s book Pédagogie institutionnelle, Mise en place et pratique des institutions dans la classe [1995], interesting examples of “monographies” can be found, accounts of events inscribed in the framework of their pedagogy. Grounded with transcripts of spoken words made by young pupils and placed in context, the analysis is never done by a single person at the height of his or her expertise, but by several members of a team. Discussions are therefore never peremptory, reflecting uncertainties, ambivalences and complexities. Scientific-based books or notions, notably drawn from psychoanalysis, are then referred to, so as to enrich the debate and help understanding, but they are never considered as absolute truth, but they are just juxtaposed as elements among others in the collective analysis of complex and singular events. The pupils’ spoken words are in this manner always put to the fore.

Report, Inquiry, Research

Artists associated in particular with ephemeral forms face difficulty accepting the principle of documenting their production. For example, in the world of improvisation, the publication of a recording seems completely at odds with the notion of a situated act, performed in the present and never to be repeated in this form.[3] The documentation of an event seems to imply that it should serve as an exemplary model for subsequent events. Modeling is viewed as susceptible to creating the conditions of servile conformity to the established order in the immutable repetition of the same things. The diversification of the objects of documentation (observation accounts, discussions, consulting archives, reports on neighboring experiences, related texts, videos, recordings, etc.) tends to cause the idea of model to disappear in favor of that of inquiry. It gathers a whole ensemble of materials[4] that may not seem interesting at first sight, but that are essential in defining the context in which the action takes place.

In the call for contributions, we had considered exploring different modes of presenting research contents to the public, whether artistic or linked to other academic fields, whether informal or as part of university-style formalization. These different ways of reporting and documenting the elaboration of a practice to honor the processes of inquiry and research that often remain implicit, are not easy to invent.

The ways of reporting are also difficult to collect. In the music world, the almost magical phrase “we do it this way” is often pronounced. But without an instrument at hand, how to explain this manner of “doing it like that”? Recording and transcribing are our usual tools of inquiry. Our meetings and interviews usually take place in life settings (houses, apartments, cafes, videoconferences, etc.) where the conditions are not optimal, since there is a lot of interfering noises that come to perturb the understanding of recordings during transcription.

Experimenting with different means of presenting research as an alternative to the sole “thesis” presented on a text written according to the current rules set up by higher education institutions remains a very important objective for us. The aim is to present objects that encapsulate the essential artistic and conceptual contents of a given practice, without revealing what specialists consider as relevant detail. We can envisage objects capable of being apprehended by an audience and giving them the desire to visit further the content of a narration, its analysis, and its various accompanying documents. Such objects can be for example a lecture/performance, a mix-media work, a collage, an audio file, an animated text, etc.

The Contributions

The edition is organized in five categories:

- Otherwards-Return.. Three articles on Africa and the back-and-forth between this continent and the rest of the world.

- InDiscipline – Flux. Two contributions deal with the interrelationships between artistic disciplines, which tend to be “undisciplined” in improvised forms. More specifically they address the relationships between dance and the environment, and between dance and music.

- Fabulate – InQuest. This category covers research concerns ranging from academic formalization to more informal approaches. For the time being, it contains only one article.

- Context – FabBrick. Three articles in this category deal with the invention of “dispositifs”, i.e. situations elaborated from a particular context and involving the people who take part in them in creative ways linked to their practice.

- Electro – Tinkering. Two articles deal with the use of electronic and digital technologies in artistic practices.

A final category, which for the time being contains no contributions, Trajects, will deal with projects that take place in several more or less remote locations and imply that the participants travel, enabling reflection before, after or between the actions taking place in the various locations.

Here, in no particular order, is the presentation of the first ten contributions:

Emmanuelle Pépin and Lionel Garcin presented a lecture/performance on the relationships between dance and music. The performance was based on a dialogue between a dancer and a musician improvising together, exploring and demonstrating dance/music relationships in acts. The actions relating the dancer and the musician during the performance were not precisely predetermined: it was a real improvisation, yet one in a long series of improvisation mixing dance and music by both artists (not exclusively in the format of this particular duo), over a very long period of time. At certain points of the performance, Emmanuelle read aloud extracts from a text she had prepared ahead of time, choosing these extracts at random in the spirit of the moment. She also improvised spoken words inspired by her text while dancing in space. Lionel, meanwhile, continued to improvise sounds while moving in space, taking care not to cover the enunciated text. The text itself was situated in an “ecotone” (or edge) intertwining the presentation of the elements in play and the description of physical, bodily and acoustic phenomena, all this unified by poetical formulations. The principal interest of this kind of performance is that the act of “saying” is completely inserted in the midst of what is danced and musicked, but also that the “saying” in progress is directly put in practice in the dance and music performed (without, however, there being a direct relationship between words, sounds and movements as a form of pleonasm). In a single movement, the explanatory text in its poetic form, and the unfolding of the dance and music materials (and their theatricalization) form a unified whole, without avoiding the presentation of what constitutes its complexity.

The three contributions concerning the back-and- forth journeys between Africa and the rest of the world, that is the interview of Djely Madi Kouyaté, the commentaries on Famoudou Konaté‘s book, and the article by Lukas Ligeti describe long life journeys full of ambivalent events. All three are personalities who grew up in traditional environments – Guinean villages for Djely Madi Kouyaté and Famoudou Konaté, and the European intellectual elite for Lukas Ligeti (who is the son of the famous composer) – and who set off on “adventure” towards the rest of Africa, and then the rest of the world for the first two, and to several African countries for the latter. In all three cases, the journeys brought out contradictions due to culture shock.

Djely Madi Kouyaté, after growing up in the tradition of a Guinean village, when he joined the group Kotéba in Ivory Coast, had to face a process of bringing together practices originating from several African countries and the development of procedures linked to spectacle and technologies influenced in part by Western culture. The group toured Europe extensively, which eventually led Djely Madi to settle in Paris, where he had to interact in greater depth with its ambient culture. This raised the question for him of how to retain the richness of his own tradition despite the few adjustments he had to accept.

The life story of Famoudou Konaté, is very similar: he is selected in his village to be part of the Ballets Africains, which brings together the best musicians and dancers from independent Guinee. This ensemble tours around the world several times and allows him to be recognized as an international djembe virtuoso. He then became an independent musician and started also to be involved in teaching the fundamental basis of his tradition in Africa and Europe, to ensure its survival in a world of globalized culture influenced by electronic media.

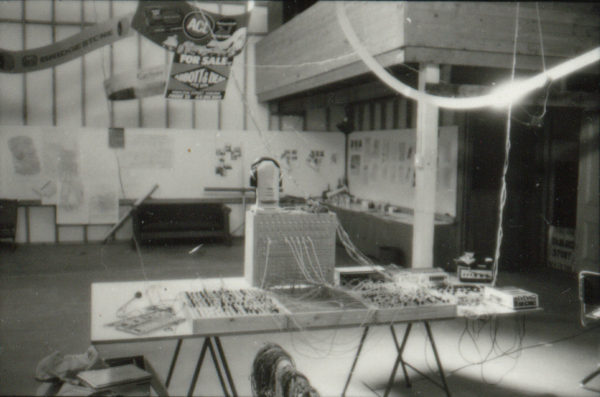

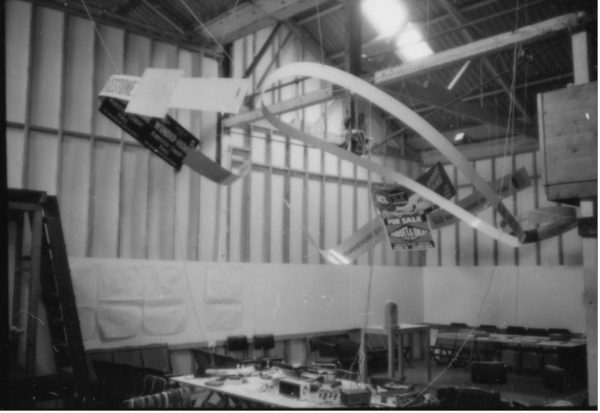

In Lukas Ligeti‘s case, he came to Africa with his own representations linked to ethnomusicological studies and composing pieces influenced by African music. Through contact with African cultural realities, he had to adapt his practice as a percussionist, composer and electronic music practitioner to African contexts that blend traditional practices to the input of various technologies linked to electricity. Then in return, this raised the question of how all these elements can be taken up in the context of Western experimental music.

Another approach to documentation was chosen in the case of the “Tale of the ‘Tale’”,, as a result of a series of four separate interviews to the four protagonists of the immersive performance “Le Conte d’un future commun” (The Tale of a Common Future), Louis Clément, Delphine Descombin, Yovan Girard and Maxime Hurdequint. This collaborative project was based on ecological issues linked to the future of the planet, with the particularity of regrouping personalities already extremely close to each other in terms of family ties, friendships, belonging to the same networks or geographical proximity. But the four parallel accounts of the performance’s lengthy production process highlighted differences of perception of how things actually happened. Each of them had built an affabulation of the role and position of the others, and in their narratives staged fictitious conversations to describe the elements of discussions and interaction required to bring the piece to life. These differences were not the expression of disagreements concerning the project itself in artistic terms or political content, but rather subtle nuances of sensibility. In particular, the account of Delphine, the storyteller, often took the form of a series of “tales” during the interview, not in the sense of inventing fictional situations, but rather in the use of a certain narrative style to convey the information she wished to give us. Therefore, on the part of the PaaLabRes editorial team, the idea came to reorganize the different interview transcription texts of interviews in the form of dialogues in what could resemble a tale describing the fable of the “Tale”.

The same subtilities of nuances can be found in the account of dancer Min Tanaka’s creation of the Body Weather Farm in Japan, by three dancers – Katerina Bakatsaki, Oguri and Christine Quoiraud – who participated to this project during the period 1985-90. Two videoconference sessions took place, separated by a time span of nine months, this time conducted jointly with everyone present. Both encounters were in English, with Nicolas Sidoroff and Jean-Charles François present for PaalabRes. None of the people present spoke English as their native language and all expressed themselves with strong foreign accents (a Greek women living in Amsterdam, a Japanese man living in Los Angeles, and three French people living in France). Hence difficulty in the editorial realization to access a clear and precise meaning during the transcript of the audio files. Additionally, remembering the exact circumstances of events that took place a long time ago was not an easy task, and each artist’s narrative reflected three different ways of looking at this fundamental experience in their life right up to the present time. For this reason, we felt it necessary to preserve as far as possible the diversity of the narrative styles used by the three protagonists. What’s more, the views that the two “paalabrians” musicians had on things were somewhat divergent than one of the three dance artists: the meaning of the same terms in dance and music is not of the same nature, and the perception of the relationship between dance and music can vary a lot depending on the field one belongs. The total ignorance of the two musicians concerning the circumstances surrounding the creation of the Body Weather farm, led to some interesting debates on the presence or absence of “commons” in Min Tanaka’s group at the farm, on his determination never to fix things in definitive forms, and above all on the idea of not creating situations where a power exercised by anyone would be imposed itself on the whole community. It is the absence of obligation, nevertheless combined with the necessity of absolute engagement at all times, with whatever actions were undertaken, which seemed to have been the main force at work behind the Body Weather idea.

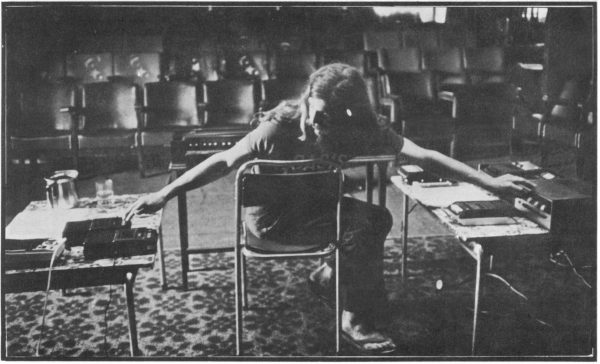

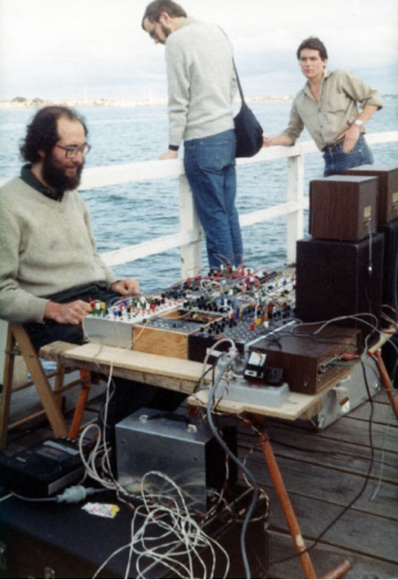

Warren Burt, who describes himself as a composer, performer, instrument builder, sound poet, video artist, multimedia artist, writer (etc.), and above all as an “irrelevant musician”, traces the recent history of the fantastic evolution of sound technologies, showing how they have influenced throughout his life his own aesthetics and political positions, in the realization of very precise actions. His militantism for an immediate use of the least expensive, most democratic tools made available by technology never changed: the use of the most ingenious, yet simplest tinkering, aiming at the richest possible aesthetics, with the cheapest utilizations possible in terms of money. Low-cost democratic access, impossible during the 1970s except for a privileged few working or studying in collective studios housed in big-budget institutions, is now becoming a reality for a large part of the world population, thanks to personal portable computers. But ironically, this access that was initially considered to be necessarily experimental and alternative, now that everybody has the ability to manipulate sound (and other objects) at will, is in grave danger of becoming nothing more than a generalized conformism generated by manipulative media.

The recent evolution of new sound technologies has led to the development of interface tools (theremin, smartphones) manipulated by performing musicians controlling machines and distributing sounds in space. The sonorities, determined by the composer and stored in a particular electronic system, are no longer directly produced by the instrumentalists who then become collaborators of the composer in determining what will actually happen during a performance. This new situation changes the conditions of the relationship between those who elaborate particular systems, those who build the appropriate technological tools to realize them, and those who implement them on stage in real time. These aspects of collaboration were the subject of the encounters with Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean Geoffroy. In retrospect, it would have been necessary to include in the interview a third person responsible for the technological construction of the new lutheries (Christophe Lebreton). In the future, there is the possibility to make up for the absence of this third facet of the collaborative musical conception.

In the minds of these two musicians, Jean and Vincent, the boundaries between creation and interpretation have become porous, but at the same time they don’t call in question the fundamental separation between composer and performer that is characteristic of Western music. In this manner, they are part of a historic continuity within this style of music, because collaborations between composer and performer, and also with the instrument builder, have often taken place in the past, despite the gradual specialization of roles in their professional function. As with the music based on processes of the second part of the twentieth century, the composer doesn’t completely determine the events that will occur on stage but proposes a regulated sound architecture into which the performer must creatively enter. The instrumentalist becomes a sculptor of sound matter in real time, a stage director of the system’s data, which creates the conditions for a new virtuosity and thus stands out from the use of interfaces (as in certain installations or videogames) by the general public.

The effective encounters of differences (cultural, artistic, economical, of geographical origin, of research content, etc.) in shared practical situations is of great importance in relation to today’s context. In all cases, whether in the encounter of different artistic domains, or of different aesthetics, or of different community groups, or again that linked to the reception of refugees, it’s necessary to invent a practical ground for mediation and not simply juxtapose or superimpose the diversity of expressions. In this manner, you may avoid the domination of one human group over another in a dual movement of respect for different expressions and of development of a common practice between groups based on principles of democratic equality.

For over thirty years, Giacomo Spica Capobianco developed actions to give young people of underprivileged neighborhoods access to musical practices in accordance with their aspirations, by enabling them to invent their own forms of expression. He has always been concerned with connecting these youths with practices of other spheres of society. He organized encounters between groups of very different styles and developed with the members of the Orchestre National Urbain improvisation situations that made possible for groups to work on common materials outside their principal cultural references. The document included in this edition, Collective Nomadic Creation, is the result of an action conducted by the Orchestre National Urbain, which took place during the Autumn 2023 bringing together young refugees from various shelter centers with the students of the CNSMDL (Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Lyon), and of the Lyon II University. It presents texts by two of the project’s observers, Joris Cintéro et Jean-Charles François and a video realized by Giacomo Spica Capobianco and Sébastien Leborgne featuring a series of interviews with various participants and extracts of music and dance actions that took place during this project.

We publish an extract from Karine Hahn‘s doctoral thesis on “Les pratiques (ré)sonnantes du territoire de Dieulefit, Drôme : une autre manière de faire de la musique.” [The (re)sonating practices of Dieulefit territory, Drôme: another way to make music.] The title of this extract is “The Metronome Episode”, in which she relates the unexpected apparition of a metronome at a rehearsal of a democratic fanfare. The metronome-object, brought in by one of the group members, drastically bursts into the scene of the practice of an ensemble that usually vehemently resists any external authoritarian imposition. Karine Hahn’s analysis of this event takes place in a context where she made the deliberate choice to be part of this “Tapacymbal” fanfare, both to experience a practice from the inside in an epidermic manner, and to be able to observe it from a more detached viewpoint. She breaks away from an oft-stated rule that, to do research, you should not get involved in the objects you are studying. If she is part of the group to be observed, she is in danger through this experience to be emotionally in solidarity with the problems they encounter, and if she remains outside, she is in danger of not really understanding what is at stake. Often researchers external to their subject matter are unable to put forward the questions that are relevant to the group they’re observing, and when they attempt to reveal the implicit structures at work, they tend to tap outside the cymbals. Karine Hahn’s position in the group precludes any overhanging approach, her position of “learned” musician and scholar issued from the conservatories aiming at professional life in music is completely put in question by a situation that awakens her own negative attitudes towards the oppressive use of the metronome. The experience of the group facing this tool, which she has to endure, results in completely challenging her representations and changes the nature of her expert eyes. This doesn’t modify her knowledge but puts it in perspective in the light of a context. It’s in the sense of this tension between the inside and the outside of a given practice that the militantism of the PaaLabRes collective concerning “informal” artistic research is situated: only actual experience can produce a knowledge of the issues at stake, and then you have to be capable of detaching yourself from it in order to develop reflexivity.

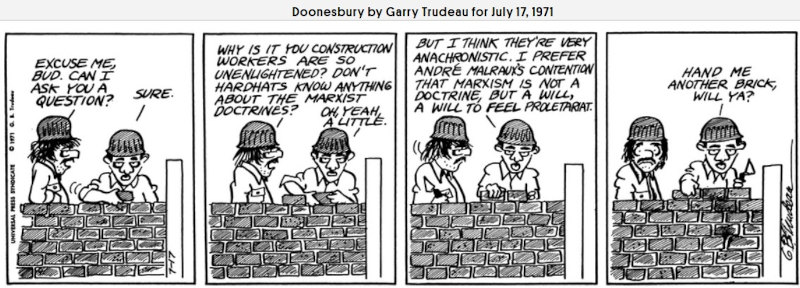

To conclude this round-table survey of the first ten contributions to the fourth edition, the two main editors, Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff, present L’Autre Musique, an account of a workshop in which the situations of collective artistic production are susceptible to provoke meaningful discussion on the subject of a particular issue, in this case graphic scores and their actual implementation in performance. The experimental hypothesis was as follows: the juxtapositions and superimpositions of research accounts (as is so often the case in the usual formatting of international conferences) fail to achieve meaningful debates. They remain in the realm of information rather than producing in-depth exchanges of ideas, because no common practice takes place, creating a context where the same objects are discussed with full knowledge of the facts. It’s from a common experience that different sensibilities to actions that are effectively lived together can emerge, whereas passive listening of academic presentations tends only to produce polite reactions (or definitive rejections).

Therefore, the paalabres.org fourth edition makes a modest contribution to exploring the various possible ways of reporting on practices, trying to find editorial solutions that are respectful of artistic content. The often-elusive ideal is to find ways to “put into practice” reporting and documentation in processes identical to those of action and research, to find a happy coincidence between artistic objects, narratives of practices and critical reflection.

PaaLabRes Fourth Edition, Future Contributions

Several contributions are currently under development:

- Pom Bouvier, back-and-forth Lyon – St Julien Molin-Molette between listening to environments and improvisations that immediately follow.

- György Kurtag Jr, work on live computer music production with young children.

- Yves Favier, Jean-Charles François, György Kurtag and Emmanuelle Pépin, “CEPI Trajects” a series of encounters around dance/music/sceno-active improvisation in Valcivières, Bordeaux, Lyon, Esino, Nice, Budapest and Cabasse. Journeys between places, a special time for reflection.

- Reinhard Gagel, “OHO! Offhandopera – Impromptu Music Theatre”. How to improvise an opera.

- Karine Hahn, continuation of the publication of excerpts of her thesis “(Re)sonating Practices on the Dieulefit (Drôme) Territory: Another Way of Making Music”.

These contributions will be published as soon as possible.

Other contributions are being considered for the future:

- Anan Atoyama, her work on the occupation of stage space and issues of climate migration.

- Jean-François Charles and Nicolas Sidoroff, on live musical accompaniment for silent films.

- Marina Cyrino and Mathias Koole, lectures/performances on the flute and guitar in improvised music.

- Kristin Guttenberg, on her practice of dance/music improvisation in unexpected spaces.

- Anan Atoyama, Vlatko Kučan and Jean-Charles François on the musician’s and dancer’s body in space.

- Gilles Laval on the European journeys of his project “100 guitars” and the idea of a nomadic university.

- Noémi Lefebvre, collective readings aloud from her book Parle.

- Mary Oliver on her experiences of musician improviser with dance artists.

- Pascal Pariaud on working with children from a primary school near Lyon on producing sounds with various means.

- Nicolas Sidoroff on fanfares in political demonstrations.

- Tam Thi Pham, Vietnamese musician and dan-bau player, on her practice of traditional music from Vietnam and experimental improvisation.

The PaaLabRes Collective:

Anan Atoyama, Samuel Chagnard, Jean-Charles François, Laurent Grappe, Karine Hahn,

Gilles Laval, Noémi Lefebvre, Pascal Pariaud, Nicolas Sidoroff, Gérald Venturi.

Références bibliographiques

ARDOINO, Jacques. (1999). Éducation et politique. Paris : Anthropos Economica, coll. Éducation (2e éd.).

BECKER, Howard S. (2004). Écrire les sciences sociales, commencer et terminer son article, sa thèse ou son livre. Paris : Economica, coll. Méthodes des sciences sociales (éd. orig. Writing for Social Scientists. How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book, or Article, University of Chicago Press, 1986, trad. Patricia Fogarty et Alain Guillemin).

BOURDIEU, Pierre. (1980). Le sens pratique, Paris, Éditions de Minuit.

BODINEAU, Martine & co. (2018). « Édito », dans Agencements, Recherches et pratiques sociales en expérimentation, n°1, p. 7-9. doi.org

HARAWAY, Donna J. (2007). « Savoirs situés : la question de la science dans le féminisme et le privilège de la perspective partielle », dans Manifeste cyborg et autres essais : sciences, fictions, féminismes, édité par Laurence Allard, Delphine Gardey, et Nathalie Magnan. Paris : Exils Éditeur, coll. Essais, p. 107-142 (trad. par Denis Petit et Nathalie Magnan, éd. orig. Feminist Studies, 14, 1988).

HARAWAY, Donna J. (1988). « Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective », in Feminist Studies 14(3), p. 575‑99.

KERGOAT, Danièle. (2009). « Dynamique et consubstantialité des rapports sociaux », dans DORLIN, Elsa, Sexe, race, classe : pour une épistémologie de la domination, Paris : PUF, coll. Actuel Marx confrontation, p. 111-125.

OURY, Fernand & THÉBAUDIN, Françoise. (1995). Pédagogie institutionnelle, Mise en place et pratique des institutions dans la classe. Vigneux : Éd. Matrice.

SIDOROFF, Nicolas. (2024). « La recherche n’existe pas, c’est une pratique ! » Agencements, Recherches et pratiques sociales en expérimentation, n°10, p153-57. doi.org

1. The other dimensions are: individual, interindividual, groupal and organizational.

2. Howard Becker gave this advice concerning writing: [Consider] “who is responsible of the actions your sentence describes” [2004 (1986), p. 13].

3. This position towards the publication of improvisation recordings outside the participants doesn’t prevent the use of sound recordings as a working tool in various re-listening situations. The recording is then used as a form of mirror to reflect on the general activity of a collective.

4. Using the term « materials » [matériaux] enables to summon up more diversity and plurality than, for example, « documents », which has a strong formal imaginary, or « data » [données] that has a strong numerical imaginary. But the term of materials doesn’t work easily with a specific verb, whereas activity and gesture should be qualified with a specific verb. The verb « to document » can then be used with this meaning: gather and organize various materials at the heart of practice.

Plus forts

Plus forts