The station « Transversal » is composed, on the one hand, of a collective text written by the members of PAALabRes in the form of an “exquisite corpse” game, each contribution being visually presented in different manners, and, on the other hand, by three transversal escapes: a) a text on the notion of hybrid and on related artistic forms; b) a text with references to the “créolisation” of the world according to Edouard Glissant; and c) a text with references to the idea of plural culture, according to, among others, Michel de Certeau.

Contents:

« Transversal »: Paalabres Collective

Hybrid

« Créolisation »

Culture in the Plural

Return to the French text

Transversal – Paalabres Collective

This is a spineless concept difficult to grasp.

If one replaces “v” par “p”, one would get something that would transpierce, that would have a phallocentric impact. But a transversal line only traverses and one has difficulties to stop it in its trajectory, and to reflect upon it.

To pierce the clouds, to traverse them. To transgress.

If one replaces “v” by “f”, one would get transfer (of stocks?), transition to the inflexibility of fer-ruginous matter. But the idea of transport (travel, love-making?) imbedded in “trans” is to go in “verses” towards indeterminacy, in a peregrination of diverse perverse fevers. One would be carried away by the trans-fair.

In ball games, “transversal” means a long passing shot across the width of the field that would reverse the game. Then, one has to be clever, skillful in sending and receiving the ball. This implies not only the receiver of this pass, but also all the participants. One never sufficiently considers the things and the people that make the actions possible. We should not forget that all penalty shots at 3 points in the net are welcome, and please not on the post!

And if one starts by taking out the “n”… The noises, the images, the odors, the tastes, the contacts and the senses traverse, in reverse also, and then diverge, and do the inverse too, whether going into a trance or not.

— You said trans, transverse and salsa, vestal, transversal?

Beware, above all to not replace the “v” by a “grrrr” of aggressive transgression.

— My transversal, but what’s the matter with my transversal?

The “it” of intestinal transit should be avoided, of sonata transition, of transitory elements in sound envelopes in the acoustical domain.

Is transversal anything that cuts across perpendicularly the longitudinal axis of an elongated form. And this is very important! For example, in modern differential topology, the study of which, it should be remembered, was started by René Thom on ideas by Poincaré (Henri, the cousin of Raymond) and which is based on the notion of transverse sub-varieties. Good night.

Certain persons go as far as saying that the dislocations of the earth’s crust are transversal faults, according to cnrtl!

To go directly to something.

In musical practices “in acts”, do not believe that financial transactions are part of them.

See the synonyms of “transversal”, there is no antonym?

The notion of instability refers to something unsteady, fragile, wavering between two ideas. Should we rather understand it as “never having the expected form”; “going towards”, etc?

The idea of transversal consists in having all the terms like fragility, stammering, attempts, round trips, displacements, migrations, transfers, etc., converge in a logic of an absolutely inexorable evolution, proper to the life of practices.

To what is it opposed?

It is opposed to, say: root, race, origin, purity, original sin, DNA …

Dog – Reality is not below the animal, even if political. It is not around, it is not to be seized, it is not a framework, not a finality. Reality is something you traverse. Writing, living in general, it is always something to be traversed.

Vestal trance, vesperal tramp, Enter the versed ballad

According to who says it, it is a real travelling across, or the use of an institutional language that does not change anything.

“One arrives somewhere, one comes out again, then it continues, one does not know where it leads; I like this idea of a music that is there, that one grasps at a given moment, it opens out, and then it closes, and in fact the music continues, it continues to leave some traces.”

Situated across something

Everything would be fairly clear if within each large category of practice we were in presence of a unity of comportments and of aesthetics. Now, the diversity of modes of functioning is not organized in borders defining genres, but is expressed within each genre in itself. For example, in the jazz world, some people want to work only with written scores, and others, on the contrary, like to insist on the conditions of an oral transmission. In the contemporary music world, almost no relationships exist between those who write scores, those who improvise, and those who have chosen to express themselves with electroacoustic means. In traditional world music one can find those who are aiming to recreate the authenticity of a disappearing social practice, and those who want to adapt their practice to the conditions of our own social life. In amplified music, there are only few common points in the ways of doing things between techno, hip-hop, rock, and those who are influenced by other types of music. One could say that every day, in all domains, a new genre emerges.

Transversal is always a transfer salve,

it obliges to anoint ones own practices with improper elements.

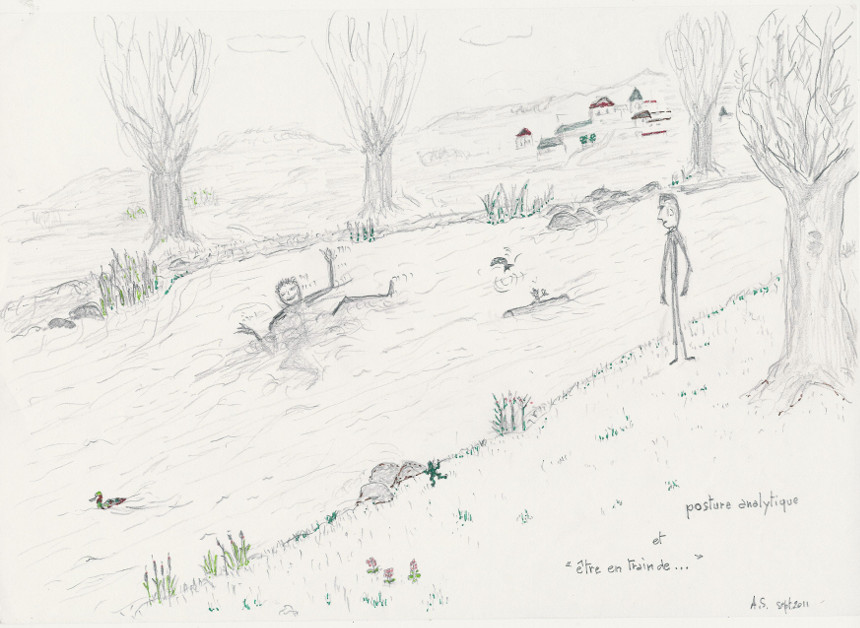

You can’t traverse, go across, without getting wet.

The traverse stains.

Traverse mucks up (traverse yuk!).

It does not always happen as expected, sometimes it slips… through the net,

it falls in the trap set…, sometimes it travels not straight.

The traversion, it is the aversion of the traverse: it has to go straight

some think that they are not transversable, the damn fools!

A music of the present time can be envisioned, as time unfolding in the making that in a way would oblige us to break with the habits of classifying in trends, aesthetics, genres, cultural influences, so as really refusing any identification to already known consensual frameworks that tend to place the artists before a paradox: one should invent in continuity, search for ideas, without exceeding the limits, create a new thread, some newness but without escaping the context organized by designations, as if these designations were there for ever, whereas they themselves appeared at a given moment, in order to get rid of other paradigms, to qualify something that the old classifications were not able to grasp.

“When a group is formed, one knows that it is composed by individualities. Each person is able to develop her/his projects alone. The equilibrium is found in co-construction, in which whoever pretends to be the leader [chef] is nothing more than a liar [menteur]: each person is at his/her place and the detail is discussed more and more. These are musical discussions in the course of elaborating propositions, each one speaks and may intervene. The decisions are always based on common choices.

In transverse, of transvermeil, through transverb, to the transvair.

Decompartmentalize

“One arrives somewhere, one comes out again, then it continues, one does not know where it leads, I like this idea of some cooking that is grasped at a given moment, it opens and it closes, and in fact, the cooking continues, it still leaves some traces.”

In the conception of transversal, it would be as inappropriate to say that such or such creation mixes influences from diverse origins, as to say it comes from somewhere or from nowhere; it is best not to search for a provenance nor for an affiliation, it is even necessary to renounce contemplating a multicultural origin, or an expression of world music. The origin of a music of transversality is here, there and everywhere: its origin is a project, and the origin of the project a desire for a project shared with musicians who bring to it their personality, their energy and their imagination.

If one utilizes it to keep the compartmentalization and the silos on the pretext of the qualifying value of some sprinkling of actions…

Contributions of the PaaLabRes collective— 2015

Three transversal escapes

Hybrid

« Créolisation »

Culture in the Plural

For an itinerary-song, towards…

For an itinerary-song, towards…