Nomadic : » What is not established, has no fixed dwelling « 1. This term when applied to the arts, can have, in the framework of PaaLabRes, several meanings :

- Artistic practices, which are inscribed in constantly reinvented processes, rather than the presence of stable, definitive and immutable objects or works (even though they might be constantly reinterpreted).

- Artistic practices, which are conceived in continuity within and outside institutions, between formal and informal learning, or which use the institutional settings for their own ends.

- Artistic practices, which refuse stylistic labels and promote the active coexistence of aesthetical positions, their effective meeting, or their blending together.

- Artistic practices which are situated in mediating spaces in between disciplines or domains of thought: any hybrid forms that are impossible to definitively classify in a single category of action; anything that aggregates theory and practice in the same act.

The idea of nomadism determines the overall form of this present “media set-up” in which this text is included, drawing from the experience of Australian Aboriginal people (see the English Editorial).

Deleuze and Guattari, in A Thousand Plateaus, in a chapter entitled “Treatise on Nomadology: the War Machine”, described the presence of a “minor” or “nomadic” science, which strongly distinguishes itself from scientific practices in the “royal” sense of the term2 :

The characteristics of such an eccentric science would be as follows: 1) First of all, it uses a hydraulic model, rather than being a theory of solids treating fluids as a special case; (…). 2) The model in question is one of becoming and heterogeneity, as opposed to the stable, the eternal, the identical, the constant. (…). 3) One no longer goes from the straight line to its parallels, in a lamellar or laminar flow, but from curvilinear declination to the formation of spirals and vortices on an inclined plane; (…). 4) Finally, the model is problematic, rather than theorematic.3

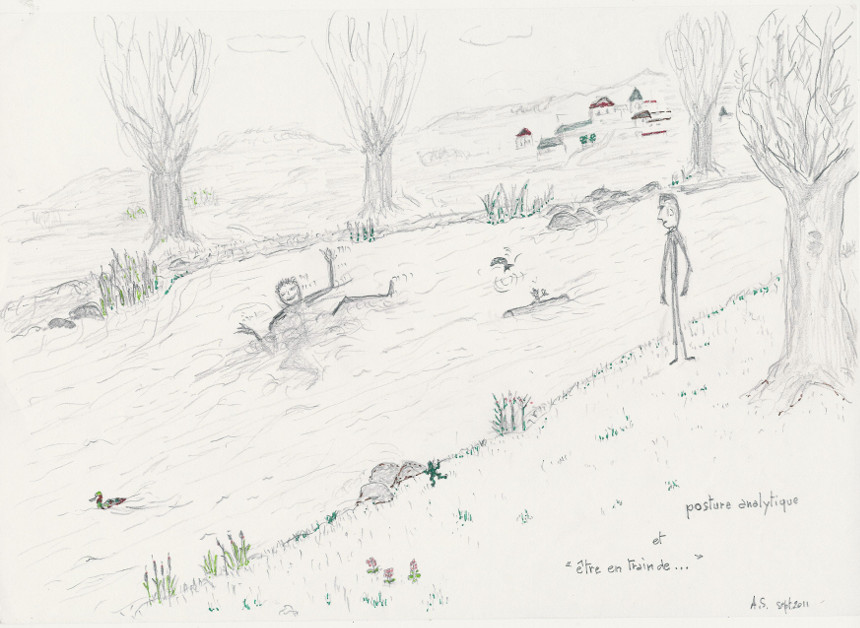

In the first proposition in this quote, Deleuze and Guattari draw on a contrast between “striated” space and “smooth” space, concepts borrowed from Boulez’s writings on music. If one takes up the proposed hydraulic image, a river consists in a partly random constant flow, from which the detail is difficult to perceive. A complex sound wave (the sound of the river for example) is of the same nature, a constant flow of sinuosity impossible to analyze without establishing some points of reference. In order to understand the river, one has to striate the space by noticeable spots distinct from each other: a rock, a bridge, an islet, etc. In order to understand sound, some discontinuity has to be established: the musical notes do not interrupt the flow of the complex sound wave, but they allow the identification by the ears of stable melodic lines, easy to recognize through repetitions, while the sound of a stream flow at a given point will only appear as a special effect, as a particular case. This is indeed one of the problematical foundations of stabilized musical parameters (precise pitch, precise durations, distinct from each other), which on the one hand are constitutive of Western musical notation, and on the other hand also entail some instable parameters, such as timbre in particular, which is inscribed in some continuity (dynamic envelopes, constantly evolving sound spectra, subtle inflections, micro-variations, etc.) and which would touch on what cannot be precisely written. This phenomenon can be interpreted, in our collective’s perspectives, as a differentiation between music centered on stable elements, with successions of identifiable notes, and music centered on timbre, on sound in itself, being understood that neither the one nor the other can dispense with the presence of a mixture of stable and instable elements: notes without timbres are too synthetic, the timbres without asperities soon become fastidious. “Nomadic” musicians would be drawn towards instable sound productions.

In the quote’s second proposition, the notion of heterogeneity in processes “in progress”, implies, in the present nomadic context, leaving indeterminate a great part of the sound production, rather than definitely fixing the detail of the contours. Rather than analyzing separately each parameter in order to control them, the approach that leaves the sonorities to unfold in all their complexity presupposes considering sound in its heterogeneous totality involving the interactivity of the parameters and not their separation. The question of heterogeneity can be expanded to social interactions, in relations to different groups or practices: social mix in a given practice, confrontation between practices, genres and styles, confrontation between artistic domains, hybrid forms, creolized cultures, cross-cultural expressions, plural declinations of culture. Nomadic would be the ones who would not seek to defend a single identity disqualifying all the others, the ones who are ready to assume several roles, taking the risk of not artificially grafting a particular role on to another, taking the risk to fully assume the imposed conditions given by each situation, without at the same time being attached to a rigid definition of each role taken separately.

Concerning the third proposition of the two authors’ quote, it relates to the concepts developed by Michel de Certeau on the differentiation between strategy and tactic. In strategy, usually imposed from above by some power, the lines are clearly defined by objectives to be attained, the space is rationalized in functional perspectives, the laws define what it is allowed, and above all what is not allowed. Tactics are answers to situations that arise, often resulting from strategy, immediately reacting to them in order to reap some benefits. Strategy traces future lines of conduct, enlightened by historical facts from the past, tactics are embedded in the meanders of reality in a continual present. The nomad thus would be the one who in a pragmatic manner allows the world to follow its course, in reacting to circumstances, with the danger of never being able to master it, nor perhaps to change it.

Finally, the fourth point of the definition, the idea of “nomadic” consists in being confronted with the complexity of things and situations, and, as their evolution occurs, in elaborating a series of questions capable of defining a comportment of action. It is not a matter of establishing some laws, or inescapable truths, some “theorems”, which will induce acceptable comportments, but of determining a balanced pathway on the crest between catastrophic precipices, in between wayward excesses on each side of the track charting its course, a pathway which problematizes complex reality. The nomad would be the one who does not simplify reality in categorical precepts easily understood, but who confronts the variable complexity of the globalized world.

The idea of nomadism is, according to Daniel Charles, linked to the notion developed during the 20th Century of “un-working” [désœuvrement], not in the sense of not knowing what to do with one’s time, or of being outside the official field of work, but in the sense of being removed from the concept of work (of art) identified by a finished object.4. Daniel Charles refers principally to John Cage, whose scores often imply processes that determine sounds or events independently of the composer and localized in the particular realization of a creative performer. The score is not any more a unique work, but can result in an infinity of potential works. In connection to this notion, Daniel Charles refers to Pierre Lévy’s work on computer applications to artistic domains, in which “the use of digital tools leads to the concept of templates for possible works ».5 The artist does not produce a work but designs a software – Pierre Lévy speaks of open source software, template or hypertext – which will generate automatically an infinite number of versions that are particular “instances” of the same structuration.

For us, the notion of nomadism, influenced by the new technologies and by world economy, has to be considered in a much wider manner. The idea of “un-working” has to be taken literally and includes the importance in today’s society of wandering and precariousness and unemployment. This also includes the cultural domain in the broad sense, in a society of leisure, in artistic forms that are often disparaged, in anonymous activities outside the public scene and the sphere of publicity.

A possible interpretation of the term “nomadic” has to do with its antonymous relationship with the term “sedentary”, as developed by Isabelle Stengers in a chapter of the seventh volume of Cosmopolitics, “Nomadic and Sedentary ». She describes this distinction between these two terms as eminently dangerous, as they lend themselves to many “misunderstandings”. Nomadic people (those who come from elsewhere in order to disturb the life routines) are rejected by the sedentary ones, but in our society, the sedentary people are those who “reject the challenges of modernity”, hanging on to their quiet little world, the nomads being those who are ready to risk changing society.6 Nomadism soon becomes an obligatory pathway towards progress and to avant-garde artistic forms attempting to make a complete break with the past. The nomadic norm could very well be considered from that perspective as sedentary. The two terms can be completely turned around in relation to particular contexts. Consequently, for Stengers, they have to be “kept in tension”.

But the sense that we want to emphasize concerning nomadism lies at the same time outside the field of institutional sedentary settlements and outside the wandering of experimental modernists without necessarily excluding them. The space of nomadism is a localized place in which the nomads move on an everyday life basis, with not much importance given to the place they might move to, as do the artisans who care about their own everyday practices without claiming to open new territories. The nomads can suddenly invade other territories perpetrating predatory raiding, but they then return to their delimited roaming at home. The smooth space is punctuated by significant objects, by striations, it is bounded by some limits. To come back to Mille Plateaux:

The nomad has a territory, he follows customary paths; he goes from one point to another; he is not ignorant of points (water points, dwelling points, assembly points, etc.). (…) Although the points determine paths, they are strictly subordinated to the paths they determine (…). A path is always between two points, but the in-between has taken on all the consistency and enjoys both an autonomy and direction of its own. The life of the nomad is the intermezzo.7

1. Translated from the dictionary Le nouveau Petit Robert, Paris : Dictionnaires Le Robert, 1967/2002, p. 1736

2. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (trans. Brian Massumi), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987 (pp. 351-423). It should be noted that the concept of “nomad” is for these authors associated with the idea of the “war machine”. It is an external space to the state apparatus with its two head figures, the king-magician and the priest-jurist. This war machine can be recuperated by the states in order to effectively carry on wars, the nomad space is a war machine which does not necessarily use effective war.

3. Ibid., p. 446-447 of the French edition.

4. Daniel Charles, Musiques nomades, écrits réunis et présentés par Christian Hauer, Paris: Editions Kimé, 1998, chapters 15 and 16, pp. 211-231.

5. Pierre Lévy, La machine univers, Paris: Ed. de la Découverte, 1987, p.61.

6. Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics II, Bononno, R (trans.), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (2010), “The Curse of Tolerance”, chapter on “Nomadic and Sedentary”.

7. Deleuze and Guattari, op. cit., p.471 of the French edition.

For an itinerary-song towards…

For an itinerary-song towards…