Situation of Collective Practice Aiming at Opening a Meaningful Debate:

A Workshop on Graphic Scores within the “Autre Musique” Seminar,

“Scores #3 « Providing-Prescribing”, 2018.

Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff

2019-2025

Translation from French

by Jean-Charles François

Summary:

Introduction

Description of the Dispositif in Place at the Start of the Workshop

Conduct of the Workshop

Phase 1

Phase 2

Phase 3

Phase 4

Phase 5

Conclusion

Bibiography

Introduction

This article gives an account of a workshop on “graphic scores”, which the two authors led in 2018. This account will be accompanied by critical commentaries. The intention here, through this workshop and this article, is to propose an alternative to the normative format of professional meetings in the world of academic research. The aim is to go beyond the simple juxtaposition (and often superimposition) of research presentations, in favor of a more direct exchange issued from collective practices enabling the opening to more substantial debates.

In the realm of artistic research, the professional meetings are today, for many reasons, completely formatted in formulas in ways that favor juxtaposed (or parallel) communication of research projects, at the expense of a real collective work resulting in debates on fundamental issues. The normative format that has slowly become instituted within the framework of these meetings (conferences, seminars) allows all the chosen persons to present their work on the basis of an equal speaking time. To achieve this, a 20-minute presentation time has been imposed in conferences, followed by a 10-minute period for questions from the public. When the number of participants exceeds the time capacity of the entire conference, parallel sessions are organized. This subdivision of time and space tends to favor autonomous groups with particular interests and therefore avoids any confrontation between forms of thought considered as belonging to categorizations that are foreign to each other. Or on the contrary, parallel sessions may involve the description of similar approaches that would have great interest in confronting each other.

The main reason for organizing international conferences in this kind of standard format relates to the usual process for evaluating university research in Anglo-Saxon universities and applied all over the world: “publish or perish”. Participation in prestigious conferences is recognized as a proof of the value of a research project, it gives access, in the best cases, to publications in various journals. Consequently, the personal participation in a conference is conditional on a formal presentation of one’s own research. The currency of exchange has become the line in the academic curriculum vitae.

The time devoted at the end of each presentation to give a voice to the people present in the room, tends to be limited to questions rather than the formulation of a debate, not only because of the lack of time, but also because of the idea that research should be evaluated in terms of proven results. If what is presented is true, it should not be the object of a discussion. The object of discussion might concern the proof itself in the context of power struggles, or throwing some light on what remains unclear, but it doesn’t concern the construction of a debate between the specificity of a research project and its inscription in the complexity of the world. The presentation of problematic issues concerning the subject at hand in a conference is left to the prestigious personalities invited, delivered from the height of their long experience, in the initial phase of the “keynote address”. In fact, debates take place during the numerous breaks, meals, at coffee machines, and other non-formal activities, most often in very small groups with common affinities. The elements of debate do not emerge under these conditions as democratic expression that would go deeper than just the informative equal-time round-table.

The format of academic conferences that was just described can be viewed as a practice juxtaposing all kinds of highly relevant information and ensuring interactions between invited people. The research presentations themselves describe pertinent practical and theoretical aspects and at the same time open the way to effective encounters. However, in these times of difficulties concerning transportation due to the climatic crisis and pandemics, you might wonder whether these kinds of information exchanges might not be limited to videoconferences. If face-to-face encounters become more and more difficult to organize, then the rare opportunities to meet effectively should open the way to other types of activity, meaning that the focus should be placed on sharing problems that we have to face, in forms of practices that are much more collective and unique compared to the day-to-day routines of each research entity.

At first sight, the idea of a workshop seems appropriate to this program, as it’s linked to the necessity for the members taking part to be effectively present in order to create, through a specific collective practice, something that makes sense and from which theoretical elements can be manipulated. But the usual workshop formulas (as well as that of “masterclasses”) is in principle focused on a practice that is unknown to the participants and which is instilled by those responsible for its animation. Alternatively, you can envision workshop formats in which the agency is only there to allow the emergence of a common practice, and at the same time the emergence of debates around this practice. In this kind of set-up, there is an initial proposition with clear instructions to collectively enter into a practice, then to allow an alternance between: doing-discussing-inventing new rules, and so on. It’s precisely what we attempted to achieve during the example presented in this article.

The workshop in question took place on March 14, 2018, during the 3rd study day, “seminar-workshop” organized by Frédéric Mathevet and Gérard Pelé, within the sound art and experimental music research group L’Autre musique (Institute ACTE–UMR 8218–Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne University–CNRS–Ministry of Culture), under the title of Partition #3 “Donner-ordonner” (Score #3 “Providing-Prescribing” or “Giving-Ordering”). Three study days were organized in the Paris area, during the year 2017-18 with the following intention:

These sessions question the relevance of the notion of “score” in relation to new sound and musical practices and, more broadly, open up to all forms of contemporary creation.

Lautremusique.net – Laboratoire lignes de recherche. Partition #3.

The study days resulted in a publication: L’Autre Musique Revue #5 (2020).

It’s in this context that we ran a two-hour workshop, with about twenty participants working in the domains of dance, music and artistic research.

Description of the Dispositif in Place at the Start of the Workshop

The starting situation of the workshop necessitated a particular approach, in order to arrive as quickly as possible at a) a collective practice, b) one that could be continued on the basis of effective participation of the people present, and c) one that could result in debates, bringing out affinities, differences and antagonisms. To achieve these objectives, the initial situation had to meet several requirements:

- The ability to describe orally the situation in a few words that would be immediately understood by all.

- The situation should define a practice that everyone can do immediately, with no special skills required.

- To develop a practice that would be at the center of the seminar’s subject matter – in this case the practice of graphic scores, from the point of view of both their elaboration and their interpretation.

- To develop a practice open to questions and problematics, and not as something imposed from the outset as a definitive solution.

Here is the description of the initial situation:

In a single simultaneous movement, to individually produce an action with three coherent elements:

- A drawing with a pencil on a sheet of paper.

- A gesture that includes the graphic production; a gesture that can start outside the drawing, include the drawing, then continue after the drawing.

- A sound sequence produced by the voice or the mouth (the vocal tract).

The action should not exceed three to five seconds. The action must be repeatable in exactly the same configurations.

This action, which combines visual art, music and dance, should be individually thought of in a coherent manner as a “signature”. In a way, it defines the singular personality of the person who produces it, it should enable any outsiders to identify an individual.

Each member present reflects for a short time to prepare his or her “signature”. The protagonists are in a circle around a very large table. As soon as everybody is ready, each signature is presented one after another several times. Then an improvisation takes place, with the rule of only being able to reproduce your own signature at a chosen time (and any number of times). The idea of improvisation here is limited the placement of one’s own signature in time. After a while, it’s possible to begin introducing variations on one’s own signature.

Conduct of the Workshop

The workshop takes place in a seminar room with a large table at its center, with chairs to sit around it, with not much space to circulate or make large body movements.

The workshop starts with an introduction to the PaaLabRes collective, to which the two co-authors are members, and with the general objective of the workshop, which is not, as in a usual workshop, to present an original practice, but is completely turned towards the possibility of a debate on graphic scores emerging from the setting-up of a collective practice. The idea is to first be in a practical situation, and then to discuss it.

The following description is based on the audio recording of the workshop. A few moments are described without the presence of the verbatim. The spoken words have been transcribed as such, and slightly modified when oral expression is not clear or sometimes partly inaudible.[1]

Phase 1

|

P:

“Is this something that’s addressed to others?”

The answer is yes, the signature must also be able to be transmitted. P:

“Will others be able to reproduce it?”

For the time being it’s not the case, but eventually it should be possible to do so. |

Time is given to allow participants to experiment with their signatures. This initial phase lasted 15 minutes (including the general presentation of the workshop).

Phase 2

|

P:

“Can we repeat the signature in a continuous way?”

The answer is yes, but it’s also possible to produce only one fragment of it. P:

“Does it mean that we are only allowed to do it once?”

No, you can do it as many times as you wish. Each time the signature must be recognizable. P:

“Do we have to continue doing the gestures?”

Yes, and also the drawing on paper. P:

“Should we keep the same rhythm, the same tempo?”

Yes, in this first improvisation, after that we’ll see. |

The various drawings produced during the first two improvisations are shown to everyone. It can be observed that these are indeed graphic scores.

A first discussion is proposed.

|

Pz:

“We can continue to experiment. By exchanging our drawings.”

P:

“By making the sounds of others?”

Pz:

« “We keep one part of our signature, but we play someone else’s score. (…) You have to take at least one part of your signature…”

P:

“You mean with the sound?”

Pz:

“From the other’s signature, you can reinterpret your own signature.”

P:

“You take your own sound, not the sound of the other?”

Pz:

“In fact, you use this score to play your own signature. [Brouhaha] You can change your movement. We’ll draw on top of it.”

P:

I do not draw on her score, I take another piece of paper, because you have to redraw.”

|

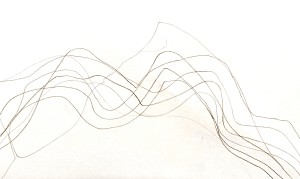

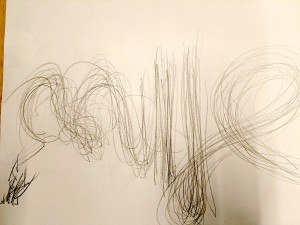

Here are examples of signatures:[2]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary 1[3]

After the two improvisations with rules determined by the workshop leaders, the only tangible element that you have at your disposal are the drawings on paper. The sounds have gone up in smoke and the gestures can be partly identified in the drawings they produced but are also vague elements that linger in memory. In these conditions, the object-paper immediately assumes the form of score, as a privileged site of what survives in a stable manner over time. The written score on paper is the locus that determines, in the modernist conception, the presence of an author. Can one find the same attitude in relation to sounds and gestures? It’s not at all certain. At the onset of exchanges of feelings, after the improvisations, one can see that there exists in the workshop a sense of respect for other’s properties: you should not draw on top of the score of another person. The score is sacred, therefore you are not permitted to rewrite over it. The sounds and gestures are not in this cultural circle deemed in the same degree of intellectual property than what constitutes the immutability of what is written on a score.

In improvisation, There isn’t any prohibition on reproducing exactly what another person is creating, even if it’s impossible to do so with absolute precision . Of course, there is an affirmation of a personal identity in the exchanges during an improvisation, but not to the point of refusing the influences exerted by other participants. You are not in a situation where the exact reproduction of a sound object or a gesture leads to the cultural death of the model. This recalls an anecdote of a trombonist having the project of learning the didjeridoo in an isolated Aboriginal community during the 1970s. The ethnologists told him never to reproduce what he heard of the didjeridoo players’ productions, as it was the equivalent of stealing their soul and taking away their reason for living. In our own practices, we are a long way from that idea.

The notion of the graphic score’s autonomy in relation to any kind of interpretation, linked to the separation between composer and performer, resulted in assuming historically a dual function: a) the graphic score can be considered as an object susceptible to result in a musical performance (or other); or b) it can be exposed in a museum or art gallery as an object belonging to the visual arts. Of course, it could also be both at the same time.

|

Pz:

“In fact, it’s as if you had a way of interpreting it with your own vocabulary, you perform with your own vocabulary. You just have one syllable, a sound or a gesture, but here you have a graphic score, and it will bring you somewhere else, because it’s not the same [as actual sound or gesture].”

|

Each piece of paper with a drawing, now becoming a score, is given to the next person on the right.

Phase 3

|

Pa:

“Replay the improvisation [just performed] and you have to make the score of the totality [of what you hear]. This is to test the reversibility [hearing to drawing, drawing to hearing]. The [recording of Improvisation 2] will be replayed, and you’ll have to make a score according to what you hear. To replay what we just performed and to draw according to what we hear.”

|

[Through this process, you can test the reversibility of the signatures: can you identify gestures and drawings in relation to what we hear?]

|

Pa:

“Draw the score corresponding to the sounds you hear. Inevitably all the sounds at the same time.”

P:

“We draw what we hear, in fact?”

P:

“We draw what we want.”

Pa:

“What you hear.”

P:

We are not obliged to use the codes of what we did?”

Pa:

“No. It’s one of the first courses that I’ve given here in 1979, it was called “sensorial approach”, you had to put your hand in a bag, and you had to draw tactilely…”

|

|

P:

“Can we keep some of them?”

P:

“Who did this one? The star! Oh-la-la!”

Pa:

“The proof is there, I think…”

P:

“The language…”

P:

“Clearly…”

P:

“Why should things be this way…?”

P:

“Are they not?”

|

The process of reading the scores continues with various comments.

|

P:

“Here we can really see a beginning and an ending.”

|

The question of representation of temporal unfolding is raised versus a global representation without beginning and end.

|

Pn:

“I didn’t think in terms of timelines,[4] in fact. And it even struck me to see things that had a beginning and an ending… Ah! they do exist!”

JCF:

“It’s the deformation of musicians!”

Pn:

“So, rightly, it was for me a question, because paper was naturally seen as a barrier… So, a spatialized writing… But OK, I had started out on something…”

P:

“You were stuck, why?”

Pn:

“The timeline. In fact, these are processes that maybe could be isolated. To be able to circulate from one to the other, to be able to go backwards.”

Pa:

“There are not many representations that are free of this timeline.”

P:

“Sound is time, after all.”

Pa:

« “Nevertheless, you can find some examples. I’m thinking of the work by T., in which there’s no timeline.”

JCF:

“But that’s not the case with the first improvisation. Experiencing time is completely different. When you improvise and make some gesture, it’s like playing an instrument, there’s no timeline. In fact, the time is now. Therefore, it’s in the reversibility that you find a very different situation.”

|

Commentary 2

Two questions emerged:

a) You can keep a score, it’s a tangible object of memory.

b) The choice between a representation based on a timeline or a global representation outside time.

On the one hand, graphic representations tend to be considered as objects with a definitive character, which can be preserved if they are judged worthy of preservation. Graphic productions tend to be seen as fixed representations of sounds that are realized over time. The dominant model is that of musical scores, which in Western perspectives constitute the privileged object for identifying a work. And with a time representation that goes from left to right, as in written texts. Under these conditions, any drawing, any image can be considered as a graphic score, on condition that the codes and modes of reading are precisely defined.

On the other hand, an issue arises of a representation based on time unfolding, versus a global representation of all the various elements in play, without beginning or end. There is a recognition that musicians in particular are formatted by the linear representation of sounds in time. There is the observation that the great majority of graphic scores is based on a timeline representation. There are few exceptions that show global forms of representation (as with topographies or cosmologies presenting simultaneously a diversity of elements).

The issue is whether the conception of time represented on a score remains the same in the case of improvised music, sometimes thought of as a present that is eternally renewed with no concerns for what just happened and for what’s about to emerge. The question of the reversibility of things depends directly on the presence of a linear visual organization. If only the present moment counts, nothing can be reversed or inverted.

|

P:

“Is it possible to try – because my brain is formatted – is it possible to do it again, for those who thought in time to be out of time, and for those who thought out of time to be in time? Because I am really formatted, then it interests me to do it without linear thinking.”

P:

“Yes, the same.” [Everyone speaks at the same time]

JCF:

“The possibility for those who wish to do it with their eyes closed.”

P:

“With the left hand.”

|

|

P:

“When I was linear, it really stressed me out. I felt tense, stuck in the line, whereas the first time it was much easier.”

P:

“It wasn’t tense for me, but I found that it produced something different. [The first time corresponded] to how I felt, but it was completely unreadable. Linear representation, it corresponds to something, it’s easier to transmit.”

P:

“So, I said to myself that when it’s not linear, I’m going to listen globally, and I realized that I couldn’t listen globally. As soon as I heard something, I wanted to draw it and I couldn’t be in the totality of the thing, I was drawn in by the details, somewhere there was still some linearity, it’s thus stayed linear.”

P:

“I think that when it’s not linear, you are more inclined to easily accept the fact that in any case your interpretation will be partial and subjective, you mix elements, it’s more pleasant, you let yourself be taken along.”

P:

“So, I worked in this way, in high-low, and that opened up the space inside. It was really very pleasant to listen and to draw according to pitch.”

JCF:

“I found that you could really be focused on the gesture of what you heard, rather than identifying the sounds. In any case, what strikes me in particular is that in the initial signature, there is really a coherence between the visual, the gesture and the sound, that you find in part in the temporal presentation, but only in part, but that you no longer find at all in the nonlinear representation… You lose the identification of the signatures.”

Pa:

“For example the duration of the sequence: what we’ve just done, what we’ve just heard, we write (describe?) how much time it lasts.”

[Everyone speaks at the same time] |

How do we perceive the duration of the recording that has just been played?

|

P:

“Does it have to be really precise?”

[Brouhaha] P:

“You’ll be able to verify. We don’t care about checking the time, the question is to know who’s the most accurate. You have to write it down, otherwise we’ll be influencing each other.”

P:

“Let’s write it down.”

|

On a piece of paper, all participants write the estimated duration of the recording of Improvisation 3. Results: 3’, 3’30”, 1’30” [laughs], 2’41”, 2’27”, 4’, 1’40”,2’… The answer was: 2’.

|

NS:

“The problem is that we all pretty much agree that we think that it starts on the first sound and ends with [he produces a vocal sound]. Except that, in fact, when you said: “What do you hear?”, I’d already started [before listening to the recording of Improvisation 3] . A situation of variation… Then, when do you decide that it starts and when you decide that it ends? You can read a sheet linearly like that as well as like that [paper noises as he rotates the sheets in all possible ways]. Then, after that, you find this one in the street, it’s not at all obvious that it should be read this way or that way. Then, where do you start reading? It’s not at all obvious. In a concert, it’s fairly clear, the light goes down, there’s the thing, here, yes there it is, ah that’s it, it’s starting. And on stage, people relax, ah, it’s finished. There is a real thing about the implicity of the end.

|

Phase 4

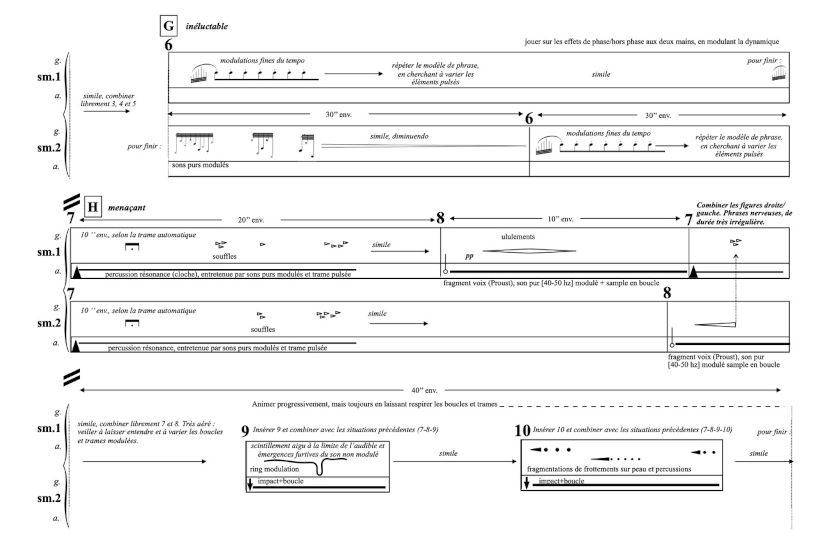

The proposition is adopted with the following precisions: groups of three are formed to realize in common a single score.

|

NS:

“What are the instructions that you gave yourselves, how did you work at it?”

P(g1):

“We divided the score in four parts. Here you can see that we divided this part [he shows]. 30” there… We agreed on the attacks…”

P(g1):

“Attacks and birds.”

|

|

P(g2):

“At first, it’s crap, because we are three and there are approximately four lines. We decided that the fourth line would be a sort of reservoir… (…)”

P(g2):

[In English:] “Sometimes I used the score, sometimes I improvised…”

P(g2):

“So, each of us had a line and a playing mode, and then from time to time we’d pick up on the fourth line, therefore we were improvising…”

P:

“Oh! yeah, organized!”

P:

“You agreed to improvise!”

P:

“I only do that. To each her or his own way!” [Laughs]

|

Commentary 3

Apart from the ironic tone, which suggests that you should not take spoken words too seriously, we can see that there are difficulties in considering the possibility of middle paths between composition, meaning here that things are fixed prior to the performance, and improvisation, which must remain free of any preparation. This way of thinking may be due to the tendency to consider on-stage the performance as absolute, erasing all the various mediations necessary for it to materialize. Whether the performance is a composition or an improvisation makes no difference, the underhand “tricks” must remain backstage, otherwise the mystery of the production presented on stage could suffer. Improvisation in particular, because it implies an absence of preparation of precise events, is often considered not to have resulted from previous events, such as education of the artists, their technical exercising, the elaboration of their own sound or dance style and repertoire of possibilities, their career path, the interactions they may have had in the past with their colleagues, or even the organization of rehearsals.

|

P(g3a):

“We didn’t use any translation. We took the thing as it was.”

JCF:

“Without discussions?”

P(g3a):

“We simplified things, we just said: we have three categories of registers, three types, and then we just read directly.”

|

|

P(g4):

“Well, our procedure was just to say that we’ll all start there.” [Laughs]

P(g4):

“I said to myself that it looks like spoken words. In fact, it really was like the writing of a language.”

P(g4):

“Yes, we thought that was the way to do this.”

P(g4):

“I thought of a radio show on Radio Campus Paris…”

P(g4):

“Still, I found this very pleasant to do. I wanted to continue.”

P:

“But you took a score that wasn’t yours.”

P(g4):

“We did it on purpose. We chose not to take our own score despite the instruction.”

P(g4):

“I didn’t see that. I thought it was better for all three of us to be neutral.”

Px:

[Participant outside group 4, the one whose score was used]: “It disturbed me a little, because I had a very precise idea…”

P(g4):

“Therefore it was your score”.

Px:

“Yeah, I didn’t think that you could do things so well. It’s terrible. Because of you I’ll presenting my projects all over the place, and making monumental flops…”

P(g4):

“It’s not just the score, there are also the performers!”

|

Commentary 4

Here, you are right at the core of the difficulties surrounding graphic scores. Is their principal link in terms of creativity relevant to composition on written scores or to the interpretation of graphisms? Are they really the occasion of negotiation between graphists and interpreters on reading codes or on the limits of their respective roles? If the ball is completely in the camp of the interpretation of scores, left to the world of the instrumentalists, vocalists, sound artists, and dancers (etc.), then any result is acceptable, including any aberrant reading of graphics (for example play “Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way…”). Graphics don’t count, if you cannot link eventual interpretations to visual signs. In this context, Nelson Goodman (1968, p. 188) analyzed a graphic score by John Cage (as part of the Concert for piano and orchestra, 1957-59) as in no way constituting a notational system, which according to him, should guarantee the ability to recognize a musical work each time it’s being played in relation to the signs present in the original score.

Historically, the composers who were pioneers of graphic scores (notably Earl Brown and Morton Feldman) were not satisfied with the sound results, when their compositions lacked any particular codes that would have obliged the performers to respect them. This happened at the very moment when the performers were not yet able to really understand what was at stake, to really perceive what was expected of them. Later, Cornelius Cardew, while he was himself a performer of his own music and collaborating with many performing musicians, developed a graphic score, Treatise (1963-67) resembling an anthology of graphic signs, an utopian version of a complete freedom left to performers (see paalabres.org, second edition, Treatise region). According to John Tilbury, who was one of the important performers of Treatise, the instrumentalist is faced with a double bind between respecting the codification of signs and improvising by ignoring the written signs. The performer, faced with an absence of codes given by the composer, is in a situation on the one hand of the impossibility of being pedantic by assigning for each sound on the score a singular sound (this for 193 pages!) and on the other hand of a moral impossibility to ignore totally the content of the score. Such was the situation of Eddie Prevost who, being completely immersed in the sounds of the music that was unfolding, started to improvise taking less and less account of the visual aspects contained in the score (Tilbury 2008, p. 247).

|

JCF:

“The idea was to go across the score, to have only whispering, to go across and have a silence before and after.”

NS:

“In fact, we decided to do that, but we’d completely forgotten that here was written a 4’15”. So, we had to do that. And after that, I said to myself: well, no… it doesn’t work, then why not make a gesture.”

P:

“But the story of the silence is that you perhaps didn’t read correctly, it was in 4/4 beats.”

|

Commentary 5

Thanks to this narration, the question of the ownership of what has just been performed is raised. You can detail the “dissemination of author’s right” (Citton, 2014) associated with the latest performances.

Let’s go through the workshop performance’s narrations in reverse order. If you tried to tell things chronologically, how would you determine the beginning? And why at this moment, and not a little earlier?

Here is the account going back in time:

• [Phase 4] 3 (or 2) people collectively invented to play starting with…

• [Phase 3] … signs on paper written by a different person, starting from…

• [Phase 2] … a recording produced by the entire group, starting from…

• … a proposition from one person to experiment a second time, after…

• … discussions and sharing of everyone’s realizations…

• … of a first proposal from another person to represent on paper what the group just performed, starting from…

• [Phase 1] … an initial protocol of two people, the workshop leaders, starting from…

• … trial-and-error (with plural multiples) in different situations of this same idea of protocol…

If you try to list all the instances in which we’ve used this protocol of signatures, it exceeds a dozen situations, and by far the fifty or so people involved in various ways in such experiments. All the proposals expressed have influenced us in determining the content of the workshop of this day of March 2018. It even happened that one of us two was not present to the experiments that took place, but had only a report on them: that’s another form of influence…

This already long journey insists on actions that can be categorized as artistic. But you should also consider, for example: the size and form of the room (organization, architecture), the way the furniture is laid out (according to what occurred beforehand and what will happen after in this room), the circumstances of the lunch break, the style of paper and pens, felt pens, pencils available, the life fragments that each person brings into the room, etc.

After this little narrative-panorama leading to these performances, how to answer the question: to whom do they belong? If you consider this question as interesting, it is certainly extremely complex. But you can also consider this narrative-panorama (and so many others) as blowing up the notion of property rights. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865)[5] long ago showed already in detail “How property is impossible” (in 10 propositions, his chapter IV, 2009 [1840]).

Phase 5

|

NS:

“In the questions raised at the beginning, I noted the issue of notation, we haven’t stopped taking notes, we’ve got lots of well-filled papers. I raided my aunt for her old sheets of paper from the 1980’s. I said to myself: I’m going to take that and see what to do with it, but in the end, they all have been used! So, we have shuffled a lot of ideas, in fact it was notation in relation to creation, to interpretation, and so on. Maybe we can go back over what each of us experienced this moment on these things, and then there’s the idea of notation in the “Providing, Prescribing” context, which was the theme of this seminar. Then, how do you understand the idea of “Providing, Prescribing” in relation to what we did, what each of you have experienced what we have done. Perhaps, we could go round the table, without any obligation to speak. We can dialogue together.

P:

“I’m completely convinced by what we’ve done. My impression is that I don’t have enough hindsight to be able to put the right words on what happened. In fact, many very different things happened. In any case, it was a great moment in terms of time and exchanges. For what is “prescribed”, we all had to sort out what we had, or at least to be obliged to make some choices. We all had to go through the graphics, especially during the last part. In any case, in terms of form, presentation and method, I find it quite convincing. Or it would need perhaps more time for being able to clarify all that just happened.”

P:

“I pass!”

P:

“It’s really cool. The question I have is: how could you go from this kind of experimentation to a creation in the sense of a spectacle, of a public performance? It’s extremely interesting to do, to practice, and I suppose that it gives a lot of matter to experiment with… so that each person can propose things. Then, around this table, there are a number of us who are already used to graphic scores and to their interpretation. I’m wondering how you go from there to turn it into an artwork. And also, about what Frédéric [Mathevet] said about what was good about graphic scores, that it could enable us to take a step aside when improvising and to invent new things. In fact, I wonder if it really allows the invention of new things. Here, in spite of everything, whatever happens, you always end up in the same kind of things…”

|

Commentary 6

Once again, you must face the ambiguity of meaning in the context of the use of graphic scores, between the presence of a score, which in the Western modernist perspective constitutes an “artwork”, and the multitude of possible interpretations, which underlines their opening up to experimentation and improvisation. For the participant who has just spoken, experimentation should lead to a definitive artwork before it can be presented on stage. But at the same time, for him, the experimentation in itself seems an attractive activity.

The first question that arises in this context is about the “new”: the value of an artwork is not in the repetition of what already exists, in the plagiarism of scores already written, but in bringing in new elements. In the case of experimentation and improvisation, the concept of the new might be more modest: you are in the presence of micro-variations around already existing elements that are inscribed in a context of immediate collective production. This context is susceptible to generating moments that are not so much conducive to the creation of new perspectives as the creation of constantly renewed situations. So what are the values specifically linked to graphic scores interpretation? Do they not open up a space of freedom, away from the qualitative evaluation considerations of recognized historical artworks and the requirements in play at the level of their performance? In what way are the performances realized during the workshop less valuable than a lot of performances on stage?

The second question concerns the hegemony of the public stage, what we call here “live spectacle”, a highly marked inheritance from what has been developed since the 19th Century. Not only does the existence of a score only make sense if it’s performed on stage, before a public that has access to its publication, but in the case of improvisation, the only intangible element is the performance “on stage”, in presence and in the present, as the only space in which improvising makes sense. But in the case of improvisation, there’s some worry concerning the feeling that the audience isn’t included in the process, that situations should be developed where everyone present is being part of the collective production. Then, the pleasure of experimentation as such can be viewed as an alternative to the stage and to the elaboration of an “artwork”, on condition of finding ways to include the public as an active member in the process, and to break out of the logic that separates professionals from amateurs.

Jean-Charles François explains the context in which the initial situation was elaborated:

|

“Simply, one of the contexts in which we did this, was on the occasion of an encounter between musicians and dancers (2015-17 at the Ramdam near Lyon). The idea of this encounter was to develop common materials between music and dance. Hence that idea of gestures and sounds linked together. Then, one day, a visual artist joined the group. The question was: what could we do to bring him into the game? And so, we developed this situation. In fact, the project was really focused on improvisation, that is developing situations in which common materials could be elaborated to be eventually used in improvisation, over the long term. So, it was done in that context, rather than with the idea of creating a graphic work, to make a piece around graphic situation.”

|

One participant asks for clarification on the situations developed in this context:

|

JCF:

“We created a lot of protocols for entering into an improvisation in which dancers and musicians had to do something in common. Then, based on the elaborated materials, we asked them to develop freely in improvisation. We did this over 5 weekends and a certain number of situations were created. The idea of signatures was the first one we used, because it’s a good way to get acquainted with each other, to get to know the people present.”

P:

“Did it produce a lot of variety? Very different things? To what extent? Gestures, sounds?”

NS:

“Today, in the situation of gestures-graphics-sounds signatures, gesture hasn’t been developed much. But at the Ramdam, the dancers helped us to do all these things. Even starting with a table, by the end everybody was playing on the chairs around the table, we were moving around. And what’s interesting, is that they helped us to do things with sounds too, in the sense that dance intelligence is in fact already multiple. I tried to do it, but I was limited, attempting to swing, making big gestures, all the while trying to relax a little. And also the question of the specialization between dance and music: when you work on this, precisely with these dancers, the distinction between dancers and musicians is something that doesn’t hold very long, even if there is a path towards music and a path towards dance. Actually, in real life, it doesn’t hold for that long, and all the protocols we did amount to questioning these things on a regular basis.”

P:

And compared to what I said this morning [she had given a paper presentation as part of the seminar], for me, it’s the gesture, with the sound you’re talking about. Even Laban really works with sound. When I am speaking, I can notate it in terms of effort, of its pushing: ‘p… p…’; throwing, spitting, hitting, all these are vocal gestures in fact. Then, the story of the pens (and so on), it’s gesture with, even if it’s producing some sound, you can see that there’s a kind of congruence between gestures and sounds. And it’s true that I have the tendency to speak only about gestures. At the same time, it’s great to bring out the sound from the gesture. Here, I loved your last gesture, because it has a sound, a real sound. With the recording, we didn’t see it, but we heard it, in fact it’s a real sound. I think it’s good to talk at the same time about sound and gesture, also because somehow you dissect to produce two materials, which… In the end it’s not indigestible.”

P:

“So, there’s also at stake something of the order of performance. For me performance is something physical, which isn’t played like an actor plays, but which is simply a matter of putting the body into play, and this is a common state that can be found in all kinds of performance. You can have in the sound here, on the effort, you can have a gesture, that on stories, on the abilities of what you can do on a sort of production, such as a movement of the mouth, of the tongue, you produce sound…”

P:

“It makes me think of the difficulties, when working on sound with choreographers, visual artists, people who aren’t musicians, of how to communicate with others. It makes me think of working with a choreographer who said: ‘I want a fresh sound’. In fact, what he meant by fresh sound is not at all what the other is doing. So, by using either the gesture or the sound, you end up with very different images of what a sound is, what a gesture is, and then, all that allows communication between artists that are different. You understand things in completely different ways.”

P:

“I went through something similar with some architects, they were talking about a Riclès [a peppermint spirit] image: Riclès, it’s fresh!”

P:

“Chewing gum! What was really interesting for me was something I’d already practiced: to notate, then translate it again, take it again, replay it, all that… But with dance you have many scores like that, where frankly the choreographer comes up with his or her own scores. And then you look at them, and you don’t understand anything. It’s the same today, you don’t understand anything, no matter what it remains abstruse. But for me there, I thought it was a good thing to be able to appropriate a text… Because with the scores of the choreographers, you don’t dare to do it, I don’t dare. Yes, all of us work with scores, but to do anything you want with scores is very interesting. In this case, it interested me to think: ‘yes, of course, it’s unreadable, I don’t know what it is, but I’m doing it’.”

|

Commentary 7

Here, you have an important element linked to graphic scores: they allow you to “do” something, to access a “getting into action”. People in the habit of working from written, visual elements, are often at a loss when it comes to improvising, which means doing without what constitutes the basis on which they function. The score is merely the pretext (text before “the text”) for doing something, putting the emphasis on the “doing something”. The score is the means to get into action, in overcoming the fear resulting from its absence. Once this fear is mastered, once the action is effective, the graphic score can be thrown away or ignored (see the Group 2 above), as it somehow has lost its importance in relation to the action it prompted. Whether the score is “unreadable” is of no importance with regards to the realization of a “doing” that fully assumes all the meaning.

On this issue, it should be noted that graphic scores very often take on their full meaning when it comes to learning improvisation practice. As a pedagogical tool, they provide a convenient transition between the habits of sight-reading scores and doing without any written support in improvisation. As in the case of “sound painting” or gestural conducting of improvisation, this type of teaching practice tends not to liberate those who get into improvisation from the hegemony of the visual over the sonic. The principal difficulty lies not in the pathway from traditionally notated score to graphic score, but with what will take place afterwards, if the aim is to access a situation of oral/aural communication that places the essential emphasis on listening and making sounds (and/or gestures) in improvisation. This applies to the musical realm and might be very different in the dance domain.

|

P:

“You can allow yourself to interpret without the pressure of the author, to be detached from the issue of the author. Therefore, this could even be done with choreographers. Certainly, we don’t allow ourselves to do that, but it’s something that you should be able to seize, and also in a certain way, if it’s drawn in this way, it should allow you to seize it afterwards. It all depends on the approach taken. If this is transmitted, somehow, you’ll be able to seize it.”

P:

“I don’t know, it’s also designed to create art works.”

|

Commentary 8

Once again the necessity to create an “artwork” comes back, in order to be able to present something professionally acceptable to an audience. To achieve this, you need to create situations that guarantee the development of practices that are inaccessible to amateurs. Experimentation in collective workshops can be strongly encouraged provided that at a given moment a creative demiurge (term that can be declined in the feminine) will seriously take over by selecting the most interesting moments of the experimentation to produce an artistic object. Those who took part in the experimentation process now play the role of little obedient soldiers.

In the professional world, there’s a lingering tendency to sacralize the one who assumes full artistic responsibility for a collective performance. In the context of this present workshop, it is said concerning this issue, how “allowing yourself to interpret without the pressure of the author” is a delicious transgression, but that cannot be done in the framework of a professional work resulting in a presentation on stage. However, the impression of being completely integrated into the creation process persists, and that’s what can be written in the performance program notice.

These rather ironic comments having been written, then, you can also take seriously the following proposal: can a given practice reach the status of an achieved work of art while respecting the rules of equality and of democracy within a collective, in a co-construction of the final result? Can an experimental process be developed over a long term with a continuity between experimental situations and public presentations? To work in such a context, any determined “method” (of a compositional nature) will not fit. It will be necessary to continually vary the modes of interaction according to the work’s progress, as was particularly the case during the present workshop over a very short time span. The supporting tools cannot be limited to a single situation, as in the following examples: improvisation, writing scores, using audio or video support, images, narratives, charts, defining protocols, and so on. The diverse supports can be summoned along the way according to the needs of the collective. Without forgetting to include in the process all the “domestic’ elements linked to the artistic work itself: cooking, housework, children, administrative aspects, relationships with institutions, organization of the space, scheduling, raising funds, etc. Another essential element has to be taken into consideration: it will take much longer for a collective to achieve a satisfactory result, than for a composer or a choreographer working on their own on exclusive plans written down in advance. But complete achievement will undoubtedly remain unattainable, and so will emerge as the salient element of an approach which, as in the case of improvisation, will eternally restart over again and again.

|

P:

“If it cannot be interpreted, if you’re given something that cannot be interpreted in some way…”

P:

“That’s in this respect that a score is not a gift, it’s not meant to give something.”

P:

“In fact what is given is that moment when, together, in a group, you learn to build your own signs. We’ve determined ourselves our own instructions for use, and thus we’ve built collectively together a reading defined with the people present.”

Pe:

“After all, these are not only signs. We don’t know what a sign is, but according to the things mentioned by Tim Ingold, there wasn’t necessarily something of the order of the sign, there was something practical, which proceeded from movement. You don’t play with the sign, but you replay it, well, you go over it again…”

P:

“…&nbps;you translate…”

Pe:

“… you have taken the same pathway, then…”

P:

“… it’s a pretext to…”

Pe:

“… a point of entry. And also in relation to what you were saying, about this idea that it could not be interpreted and all that. This being so, there are scores that are virtually unplayable, but when you look at them, they put you in a certain universe. Perhaps, you will not be able to transform them into sound, it’ll remain a purely visual thing, but if you look in detail, you’ll see lots of scores, you’ll be able to imagine things, and after that you’ll be able to play it, it will become worthwhile to play it. Already – in front of the details – you say to yourself, this is a music that gives you something. You can also imagine that this music is a drawing. The things by Cage, where the margin for interpretation…”

JCF:

During the 1950-60s, we lived through something like this, that is, a large number of composers producing graphic scores, and they were also very frustrated by the results, because, for example, the performers tended to produce clichés, as nothing was prescribed. A certain frustration could be also found with the performers, because they found themselves in a sort of middle ground, in which you had both the imposition of graphics, but a non-imposition over its interpretation: the performers had to start with a given data that they didn’t choose. It was both imposed, and you had to invent everything. This was the time when performers of contemporary music turned more to improvisation, that is, to completely taking hold of things without the help of a composer. What’s interesting today is the renewed great interest for graphic scores, which has reappeared in recent years – it never disappeared in fact – but maybe in a different context.”

Pg:

“The term ‘graphic score’ certainly refers to something precise. For me, for example, my scores represent real graphic preoccupations. Besides, I don’t use any score-editing software, I use graphic design software. For example, I take a blank page, and create something graphic, and sometimes I make choices according to a grammar principle, but above all I make a graphic choice so that the eye is satisfied, so as to find an equilibrium, a dynamic, and so on. For me, it’s a highly coded graphic score.”

JCF:

“There’s a book from the 1970s by architect Lawrence, RSVP Cycles (1970), I don’t know if you are familiar with it?”

Pg:

“We’ve talked about it…”

JCF:

“Your approach reminds me of this.”

P:

“I really appreciated this day. With your methodology, you said that we had to physically recognize – or so I didn’t quite understand – we had to recognize each other, I don’t know what the intention behind it was.”

JCF:

“The primary intention was that we didn’t know each other and it’s a means to…”

P:

“… present ourselves.”

P:

“The signature, in a more physical way…”

JCF:

“Yes that’s it, to get to know each other in a non-verbal way, but well… it was just a beginning…”

P:

“I never did that before. I would like to do it in relation to the experience of walking. And to discuss, to select the sound, what sounds to keep, what sounds will be transmitted. To choose sounds, to be attracted to sounds. In working together, we harmonize things. But in what I’ve experienced, I cannot transcribe all the sounds at once, I have to make choices…”

|

[End of recording and workshop]

Conclusion

Within the space of two hours, it was possible to develop real practical situations, already familiar for the people present at the workshop, provoking animated discussions. These discussions focused at the same time on the immediate modalities of the practical situations, on the invention of variations around these situations, and on a debate on the aesthetics and ethics that these practices evoked on the spot. From this debate emerged all the major aspects of the problematics linked to the use of graphic scores:

- The interpretation of visual objects in dance and music domains, the relationships between ‘creators” (composition, choreography, stage direction, ensemble conducting) and “performers”.

- The question of intellectual property of graphic scores

- The multiple functions of graphic scores, between artistic production and specific tools within a more general process.

- Experimental situations in relation to professional performances on stage.

- The meandering nature of experimental situations in relation to the precise elaboration of a definitive “artwork”.

- The body presence, providing dual access to dance movements and sound production, enabling to establish meaningful relationships between dance and music in relation to a visual object assimilated to the field of visual arts.

It seems obvious that the fleeting expressions during the discussions could not imply an in-depth analysis of the concepts addressed, nor an immediate awareness of their meaning on the part of everyone present. That’s why it was necessary to take up what was said during the workshop in a series of our own “commentaries”. Interpreting what people said helps us to think but is by no means a way of analyzing or explaining what those persons think or do. The aim of opening a debate arising from a common practice and from the particular history of each participant has been completely achieved. You cannot predict what this first collective approach might have produced if the workshop had been extended over two or three days, but we’re in the presence of a fairly promising beginning.

Obviously, all the questions pertaining to graphic scores could not be tackled during the workshop, the debates have not exhausted the issues.

In conclusion, the practical set-up that we’ve just described seems to be a credible alternative to be developed during professional meetings linked to research (notably artistic). The juxtaposition of ideas, research reports, and various communications can be done through teleconferences (synchronic) and other digital tools (asynchronic). As international face-to-face gatherings increasingly become a rare occurrence due to climatic and pandemic evolutions, the invention of alternative situations where effective encounters around practices and the debate based on elements developed in common take place, becomes a very important condition of our artistic and intellectual survival.

1. In this text P= workshop participant. When someone takes the floor several times in a very short time, the identification is P+a letter (Pz for example). The only persons that are identifies by their names are the two workshop leaders: JCF=Jean-Charles François; NS=Nicolas Sidoroff.

2. It should be noted that the papers on which the workshop participants produced their signatures have been lost. The examples given are taken from a similar situation in Budapest in January 2023.

3. The exchanges during the workshop between moments of practice allow to explicit a certain number of elements connected with the situation, and a second phase is necessary to carry further the ideas that are expressed. It’s the function of the commentaries in frame, written after the fact by the two authors.

4. See Tim Ingold (2007) on the notion of “lines”. As it happens, Tim Ingold was invited to present a paper in the seminar, in the session immediately preceding our workshop.

5. “Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the ‘father of anarchism’.” (wikipedia).

Bibliography

(L’)Autre Musique. (2020). Revue, #5 Partitions. See L’Autre Musique.

Cage, John. (1957-58). Concert for Piano and Orchestra. London, New York: editions Peters.

Cardew, Cornelius. (1963-67). Treatise. Buffalo, New-York: The Gallery Upstairs Press.

Citton, Yves. (2014). Pour une écologie de l’attention. Paris : éd. du Seuil, coll. La couleur des idées.

(2017). The Ecology of Attention. Cambridge, Malden MA: Polity Press (trans. Norma Barnaby).

Goodman, Nelson. (1968). Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill (2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1976).

Halprin, Lawrence. (1970) The RSVP cycles: creative processes in the human environment. New-York: George Braziller [archive.org].

Ingold, Tim. (2007). Lines, A Brief History. London: Routlege.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (2009). Qu’est-ce que la propriété ?. Paris: LGF, Livre de poche (1st ed. 1840).

What is Property? An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government (trans. Benj. R. Tucker, 1876 [archive.org, anarchistlibrary.org].

Tilbury, John. (2008). Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981), A life Unfinished. Matching Tye, near Harlow, Essex: Copula.